Shark Presence in New England

OPEN ACCESS PUBLICATION: EARLY INSIGHTS INTO THE SEASONAL AND SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF WHITE SHARKS (CARCHARODON CARCHARIAS) ALONG THE MAINE COASTLINE

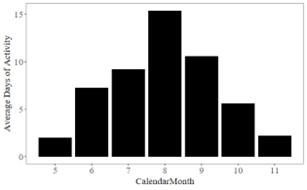

The western North Atlantic Ocean is home to a variety of marine species. One such group of animals, referred to as Highly Migratory Species (HMS), are capable of traveling thousands of miles each year for the purposes of foraging, reproduction, and finding optimal habitat. The biological diversity seen within HMS, which includes tunas, billfishes, and sharks, is some of the greatest amongst any group of fishes. From the large filter-feeding whale shark (Rhincodon typus) to the small and fast-swimming skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), HMS of all shapes and sizes can be found inhabiting the waters of the Atlantic. Perhaps the most notorious and charismatic of these fishes, particularly in New England waters, is the white shark (Carhcarodon carcharias). White sharks have been historically documented in New England, and are most often observed during the months of July, August and September (see figure below). White sharks are considered an apex predator, meaning they exist at the top of the food web with few predators. Young white sharks predominantly prey on bony fish, squid, and smaller sharks, but as they grow and mature the primary source of food transitions to lipid-dense prey, such as marine mammals.

Population Status

Concerning the global population status of white sharks, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) designates the white shark as a species vulnerable to extinction risk. There are several reasons for this classification, including a general lack of information regarding critical habitat use, slow growth rates, slow reproduction rates, and a general tendency to travel in areas inhabited by humans (i.e., nearshore). However, on a regional scale, white shark populations in the western North Atlantic appear to be in a slow state of recovery. Research suggests that white shark abundance in the western North Atlantic has increased in recent years following the implementation of shark conservation measures in the 1990's and the protection of marine mammals in the 1970's, which resulted in the recovery of New England seal populations, which are a primary food source for sub-adult and mature white sharks.

Follow this link to visit the IUCN assessment.

Research and Collaboration

The 2024 Maine White Shark Monitoring Update (pdf file) is now available. This includes program updates, deployments and sightings.

In 2020, the Maine Department of Marine Resources, in collaboration with Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, and others, initiated efforts to monitor the presence of white sharks in Southern and Mid-coast Maine waters. Each spring, scientists place acoustic receivers at fixed locations along the coast of Maine, leaving the devices submerged one or two meters beneath the surface. These receivers are designed to detect nearby acoustic transmitters, also known as tags. There are approximately 300-350 white sharks that have been outfitted with acoustic tags in New England, and when one swims within a few hundred meters of an acoustic receiver, a detection is recorded. Each winter, scientists at the DMR retrieve the acoustic receivers, download the detection data, and assess shark activity from the past year.

To further improve the management and scientific knowledge of white sharks in the Northern Atlantic, Maine DMR partners with several regional organizations to form the New England White Shark Research Consortium (NEWSRC). With access to a large variety of resources and knowledge, the DMR and NEWSRC aims to further our understanding of white shark ecology, distribution, and habitat use.

White Shark Detection Highlights

- 93 white sharks have been detected on DMR receivers since surveying began in 2020

- White sharks have been detected as early as May and as late as November

- Size of sharks range from 7’ – 16’ in length from snout to tail tip

- Sharks spend an average of 13 minutes at receiver sites before leaving, though it varies

- Receivers near Higgins Beach, Scarborough Beach, and Cape Elizabeth observed the most shark activity in 2024

Acknowledgements

Transmitter data used in this research are owned and maintained by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (MADMF), the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy (AWSC), the NOAA Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office, Oregon State University (OSU), and the University of New England (UNE). The acoustic receivers being used are property of the DMR, UNE, and MADMF, with several donated to DMR from AWSC, and historically from ASU. Deployments were made possible thanks to Justin Papkee of the F/V Pull n’ Pray, Joshua Audet of the F/V Karamel, and Michael Dawson of the F/V Lisabeth . Sightings reports are vetted with the support of John Chisholm of the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life. Allied Whale and Marine Mammals of Maine opportunistically alerted this program of instances involving potential shark predation on seals. We also thank the fishermen, beach officials, and citizen scientists who make our sightings data and receiver work possible.

Have you seen a white shark?

Please report it to one of the following:

Please report it to one of the following:

Shark Facts

- Sharks belong to a group of animals called Elasmobranchii - fish that have bones made of cartilage. Stingrays and skates belong to this same group!

- Sharks are old - the first is thought to have originated over 400 million years ago!

- Not all sharks are apex predators - some smaller species, like the spiny dogfish, are prey for larger species.

- Some sharks give live birth, while others produce eggs. In very rare instances, scientists have observed parthenogenesis; that is, a female shark reproduced without male contact!

- Sharks are important - whether big or small, sharks help to regulate prey populations and transfer energy within their ecosystem. This is important in sustaining marine environments.

- Shark attacks are extremely rare - more people succumb to injury from lightning strikes than they do shark attacks.

- Though rare, attacks are recorded - reported attacks are tracked globally and publicly compiled in the International Shark Attack File (https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/)

Shark Safety

- If you choose to swim, surf, or paddle, be aware of your surroundings

- Stay close to shore

- Swim, paddle, and surf in groups

- Avoid areas where there are seals or schooling fish

- Avoid murky, or low visibility water

- Limit splashing

- Avoid swimming at dawn/dusk when lighting is low

- Adhere to all signage at beaches and follow lifeguard instructions

- Additional advice is available at https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/reduce-risk/swimmers/

For more information, please contact DMR Scientist Matt Davis at Matthew.M.Davis@Maine.gov.