Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Species Information → Mammals → Black Bears

Black Bears

Range and Distribution

The black bear is the smallest of the three species of bears inhabiting North America (black, brown/grizzly, and polar), has the widest distribution on the continent, and is the only bear living in the eastern United States. Black bears are found in most forested areas from Mexico north to the edge of the tree line in Canada and Alaska. In Maine, black bears are found nearly statewide, but are most common in northern and eastern Maine and are rarely found in the heavily settled southern and central-coastal regions.

View a map of the Black Bear range.

Photo Credit: Paul Cyr

Physical Characteristics

Although most black bears are not much larger than humans, their weight can vary tremendously with the season of the year. Bears store body fat during the fall months to supply energy during their long winter denning period, and are heaviest in late fall.

Adult males average 250 pounds, and measure 5-6 feet from tip of nose to the tip of their tail. Females are smaller, with adult females averaging 150 pounds, and measuring 4-5 feet in length. Males stand about 40 inches tall at the shoulder; females seldom exceed 30 inches in height. Bears are compact, with stocky legs, small eyes, short, rounded ears, short curved claws, and a short, inconspicuous tail. The black bear has a straight facial profile and a massive skull. Black bears in Maine are normally black, but they are often various shades of brown to cream colored in western populations, and are even white, and blue-gray in color in coastal British Columbia and Alaska. They have a brown muzzle, and occasionally a white throat or chest patch or "blaze". Bears walk flat-footed, and their broad feet leave 5-toed tracks that sometimes resemble human footprints. Tracks of female bears rarely exceed 4.5 inches in width; males leave tracks up to 6 inches wide.

Natural History

Habitat

Black bears require forests for protection and food. They are amazingly adaptable to human presence, and are able to survive in close proximity to housing developments and suburban areas wherever escape cover exists. Maine has 69,050 km2 of bear habitat, consisting of mostly second-growth conifer-deciduous forest that provides an ample supply of bear foods (berries, nuts, fruits, and carrion).

Food Habits

Bears are opportunists, and feed on a wide range of vegetation and animal matter. Although bears eat meat, their diet is primarily vegetarian, including early greening grasses, clover, and the buds of hardwood trees in the spring, fruits and berries in summer, and beechnuts, acorns, and hazelnuts in the fall. This diet is supplemented with insects, including ants and bees (their larvae, adults, and honey), and occasional mammals and birds. Bears are not considered efficient predators, but they are known to prey on young deer and moose in late spring, and will consume carrion. Bears are intelligent, and adapt rapidly to new food sources, including agricultural crops and food placed to attract other wildlife, such as bird feeders, and untended garbage. Therefore, conflicts between bears and farmers, beekeepers and orchardists, and rural residents in the State can occur. See our living with wildlife page to learn more about how you can minimize conflicts with bears.

The fall documents a period when bears are feeding intensively to build fat stores for surviving a winter of fasting. Fall foods are especially important to pregnant female black bears who need sufficient fat stores for fetal development and milk production. The spring represents a period of food stress, as most bears emerge from the den.

Reproduction

Black bears breed from May through August, with most breeding activity peaking in June and July. Throughout the summer, males travel over large areas to enhance their chances for encountering mates. Although males become sexually mature at 1-2 years of age, most do not participate in breeding until they have reached full adult size, at about 4-6 years in Maine. Female bears in Maine become sexually mature at 3-5 years of age.

Although black bears breed in the summer, fetal development is delayed until early winter, after the female has entered a den. In January and February, female bears give birth to 1-4 cubs inside the winter den. If a female is unable to store sufficient body fat prior to entering the den, the pregnancy is terminated.

Cubs weigh about 12 ounces at birth, and depend on their mother for warmth and nutrition during the remainder of the winter. They grow to 4-10 pounds by mid-late April, when the mother leads them away from the den. Because cubs remain with their mother for 16-18 months, female bears do not breed in the summer following the birth of their cubs. Cubs enter dens with their mother the following fall. When they emerge from their winter den as yearling bears, they remain with their mother until she goes into estrus in the spring. This long period of parental care leads to females bears producing litters every other year. When beechnuts were the primary fall food for bears in northern Maine, most cubs were born in odd-numbered years in response to alternating years of high beechnut crops. More recently, cubs are born in both years in northern Maine, following several years of lower but consistent beechnut crops. Cub production has been more consistent in central Maine, where more stable fall food supplies result in nearly half of adult females giving birth each year.

Longevity

Bears are long-lived animals, capable of surviving 30 years in the wild. Their survival increases as they mature. Less than half of newborn cubs may die before reaching their first birthday, with starvation being a major cause of death. By the time bears in Maine reach 2 years of age their survival exceeds 90%, and nearly all deaths of adult bears are due to hunting or other human-related causes.

Movements

Photo Credit: Dominic Grenier

Black bears lead solitary lives, except for breeding pairs, family groups comprised of adult females and their offspring, and occasional aggregations at concentrated food sources. Females use areas of 6-9 miles squared in Maine. Although, female bears remain within or near the range of their mother their entire life, male bears disperse long distances (often up to 100 miles) as subadults (1-4 years of age) prior to settling into adult ranges that may exceed 100 miles squared. Bears often make trips up to 40 miles outside of their ranges to feed on berries or nuts (or occasionally to an orchard or field of oats or corn) in late summer or fall. When feeding on a concentrated food source, bears may use areas as small as several acres; when searching for dispersed food or mates, they can cover several miles in a day. Bears are active in late fall as long as food is plentiful. In years when fall foods are abundant, bears will feed until snow makes travel difficult, and normally enter dens in late November. If late fall food is scarce, bears usually enter dens in October.

Management

We use data collected from annual harvests and telemetry studies to guide bear management decisions in Maine. We regulate bear numbers primarily through annual hunting and trapping harvests. The information we use to assess the bear population and bear habitat is documented in a written bear management system (PDF) developed in1986, which contains criteria for decision-making and management options.

A reassessment of the past, present, and future status of bears, their habitat, and demands on the bear resource was completed in 1999. This assessment (PDF) provides the scientific basis for management goals. In 2001, the Department set new management goals and objectives to direct bear management through 2015 based upon the recommendations of a public working group representing diverse interests. A bear management goal of providing continued hunting, trapping and viewing opportunity for bears was established by 1) stabilizing the bear population’s growth by 2005 at no less than current (1999) levels, 2) creating information and education programs to promote traditional hunting and trapping methods as preferred and valid tools to manage the state’s black bear population, and 3) creating information and education programs to promote public tolerance of bears. Maine’s bear population remained fairly stable through 2005, but has been increasing over the last 5 years and our current estimate is between 24,000 and 36,000 bears.

Hunting

Since 1975, we’ve monitored bears in four separate study areas across the state. Bears were bountied as vermin until 1957, but were granted game species status in 1969 when mandatory monitoring of annual harvests began. Since 1990, Maine’s bear season framework has remained fairly constant with a 3-month fall hunting season that opens the last Monday in August and closes the last Saturday in November. The annual bag limit is 2 bears per year with one taken by either hunting or trapping or both. Bears can be hunted over bait during the first 4 weeks of the season, with hounds for a 6 week period that overlaps the last 2 weeks of the bait season, and by still hunting and stalking throughout the entire season. In September and October, trappers can set 1 foot snare or cage trap for bears. Harvest regulations are applied uniformly statewide, with no regional controls on hunting effort.

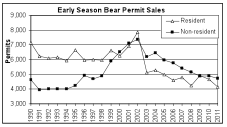

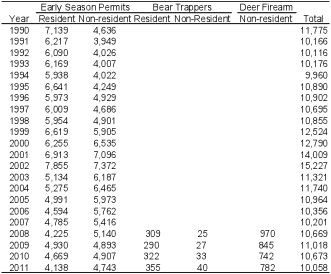

Beginning in 1990, a bear hunting permit has been required to hunt bears in September and October. For the first 8 years, Maine residents purchased the majority of permits and permit numbers fluctuated between 10,000 and 11,000 (Table 1). After the spring bear hunt in Ontario was closed in 1999, non-resident hunters became more interested in hunting black bears in Maine. Within a year, non-resident participation exceeded resident participation. By 2002, permit sales peaked at over 15,000. A rise in permit fees in 2003 (resident $5.00 to $25.00; non-residents $15.00 to $65.00) and the down turn in the US economy have likely contributed to declining resident and non-resident hunter participation in recent years.

Beginning in 1990, a bear hunting permit has been required to hunt bears in September and October. For the first 8 years, Maine residents purchased the majority of permits and permit numbers fluctuated between 10,000 and 11,000 (Table 1). After the spring bear hunt in Ontario was closed in 1999, non-resident hunters became more interested in hunting black bears in Maine. Within a year, non-resident participation exceeded resident participation. By 2002, permit sales peaked at over 15,000. A rise in permit fees in 2003 (resident $5.00 to $25.00; non-residents $15.00 to $65.00) and the down turn in the US economy have likely contributed to declining resident and non-resident hunter participation in recent years.

Starting in 2008, trappers and non-resident deer hunters are required to purchase a permit to harvest a black bear. This new permit was established to track hunter participation later in the season and to generate a dedicated funding source for bear research and management. Even with the additional permit, permit numbers haven’t returned to previous 2000 levels (Table 1). We will consider increasing hunting opportunities to meet bear management goals, if hunter participation continues to decline, especially during the early bear season.

Table 1. Summary of black bear permit numbers in Maine.

Conflicts

Over the past century, conflicts between bears and humans in Maine have lessened with changes in agricultural practices, the decline of farming, increased interest in bear hunting, and the species’ rise in status as a game animal. In addition, Maine has a small human population (1.3 million) that is mostly concentrated in the southern third of the state where bear densities are lower and therefore bear-human conflicts are less numerous. However, each year, primarily in the spring and early summer, the Department receives numerous calls from homeowners when bears have destroyed bird feeders or disturbed garbage. Most conflicts with bears can be prevented by removing common food attractants around homes.

Over the past century, conflicts between bears and humans in Maine have lessened with changes in agricultural practices, the decline of farming, increased interest in bear hunting, and the species’ rise in status as a game animal. In addition, Maine has a small human population (1.3 million) that is mostly concentrated in the southern third of the state where bear densities are lower and therefore bear-human conflicts are less numerous. However, each year, primarily in the spring and early summer, the Department receives numerous calls from homeowners when bears have destroyed bird feeders or disturbed garbage. Most conflicts with bears can be prevented by removing common food attractants around homes.

To prevent conflicts with black bears each spring (April 1-October 1):

- Bring in your bird feeders, rake up and dispose of any seed left on the ground, and store unused seed inside. If you want to continue to feed birds in the spring and summer consider using an electrified mat (MS Word).

- Bring trash to the curb on the morning of trash pickup or use a certified bear resistant container.

- Keep dumpster lids closed and do not allow dumpster to overflow. In areas experiencing bear problems consider storing dumpsters in a secure building or behind electric fencing (MS Word).

- Clean your grills and empty the grease cup after each use. Do not discard grease on the ground. Burn-off any food residue, clean blood and grease dripping, and discard food wrappers.

Each year, primarily in the spring and early summer, the Department receives numerous calls from homeowners when bears have destroyed bird feeders or disturbed garbage. Most conflicts with bears can be prevented by removing common food attractants around homes. To learn more about preventing bear conflicts in back yards, while camping, hiking, see Living with Black Bears.

Research and Monitoring Program

The Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MDIFW) is charged with managing Maine's abundant wildlife resources. One of our most celebrated and treasured animals is the black bear. Although many people enjoy an abundant bear population, too many bears can create problems for the bears and the people who live with them. Black bear management is a balancing act between maintaining a healthy and abundant population for all to enjoy, and limiting the growth of the bear population so that bear nuisance problems do not cross the line of public tolerance. A big part of managing bear nuisance problems involves modifying human behavior to lessen the number of negative bear/human interactions. This may include advice on taking in bird feeders, handling outside trash, and how to prevent damage to agricultural crops. Each fall, bear hunters enter the Maine woods in hopes of harvesting a black bear. These hunters and the rules that control their methods are the tools that managers use to ensure the bear population is not overharvested and to keep the bear population from "crossing the line".

How do biologists determine the proper number of animals that needs to be harvested? The first part of any management program is to have clear goals and objectives. Our management goals and objectives are set by interested members of the public that have reviewed and discussed the latest MDIFW bear assessment (Public Working Group). These goals are set about every 15 years. Our current management goal for bears is to provide hunting, trapping, and viewing opportunity for bears. Our population objective is to stabilize the bear population (no significant increase or decrease in numbers) through traditional hunting and trapping activities. In order to maintain a stable bear population, we must have a good understanding of the number of bears entering the population (recruitment) to replace losses. While the number of bears harvested by hunters each year is known, the number dying from other causes and the numbers entering the population must be determined by our research.

Photo Credit: Dominic Grenier

The Maine black bear monitoring program is a long-term project designed to continually gather data regarding the status of our bear population. The program began as a study in 1975 when Roy Hugie in cooperation with the Department established 2 study areas consisting of 4 townships each - Spectacle Pond (20 miles West of Ashland) and Stacyville (near Patten). Roy compared population characteristics of the bears living in these 2 study areas for his PhD. At that time, the Spectacle Pond area was lightly hunted; whereas, bears in the Stacyville area experienced heavy hunting pressure. Today, hunting pressure is more evenly distributed across the bears' range in Maine.

In 1981, the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife took over Roy's project and established a new study area near Bradford (north of Old Town) in 1982. The Department also changed the focus of the project by using radiocollared females in each study area to represent bears across the state that are living in similar habitat conditions to that study area. For example, if we found that our radiocollared females in our study area in the northern commercial forest were particularly successful in raising their cubs in a given year, then we would assume that other females living in the northern commercial forest were also very successful.

Currently, we have three active study areas in northern, north-central and eastern Maine. In 2004, the Stacyville study area was discontinued and a new study area was created in Downeast Maine (northeast of Beddington). This study area was established to address a longstanding need to better represent a portion of Maine's bear population in eastern Maine living under habitat conditions not well represented by the other 2 existing study areas.

A total of between 85 and 110 radiocollared female bears are monitored each year in all three study areas combined. Radiocollars are helpful for monitoring black bears because their secretive nature makes them difficult to observe. Radiocollars send out a signal revealing each bear's location in her den as she hibernates under the winter snow. All of our collared female bears are visited each winter in their dens, which allows us to determine the number of cubs born. Because these cubs stay with their mother for 16 months and den with her the following winter, we can also determine how many cubs survive to one year of age (known as yearlings). We tag the ears of all cubs and yearlings to identify them. Female yearlings are equipped with radiocollars, which allow us to follow them throughout their lives after leaving their mothers the following summer.

Photo Credit: Paul Cyr

We have found marked differences in reproduction, survival, and recruitment between study areas as well as within study areas over time while habitat and weather conditions change. The variables that cause these differences are many and complicated and are not easy to predict, measure, or even identify. Nutrition plays a major role in determining the number of cubs that are produced, and cub survival through their first year.

Bears in Maine utilize a wide assortment of natural foods, and the food types that are available in each study area are quite different. Traditionally, beechnut production has been linked to cub production in northern Maine, but these nuts have been less reliable in recent years and are less important in southern areas. The abundance of many types of bear foods are affected by weather, which makes predicting the food supply and cub production difficult from year-to-year. Closely tracking food production would help us explain year-to-year variations in cub production and survival. With limited funding, we can more efficiently measure cub production and survival directly during our winter den visits.

Forestry practices are continually evolving, which changes the world the bears live in and the food they depend on. Forestland ownership and market conditions are constantly changing as well, which also impacts forest resource management. Unforeseen disease or insect outbreaks may influence forest composition and harvest strategies in the future. Thus, the general nature of the forests of northern Maine and the bear foods they provide are very different now than they were years ago, and most likely will be different in years to come. The combined effects of all these complex variables on bears are most easily measured by continually monitoring the bears' successes and failures directly in their dens.

A large part of our bear monitoring program involves trapping and radiocollaring bears in late spring and early summer. Trapping bears with foot-snares allows us to collar new bears to replace collared bears that have died or that have been lost due to malfunctioning collars. Periodic trapping efforts are necessary to maintain a representative sample of bears in each study area. We ear-tag many males while trapping and in the dens as well. Because males often damage their ears while fighting, we also tattoo their inner lip for a permanent mark. These marked males offer additional information regarding their movements and mortality when they are re-encountered through hunter harvest, roadkill or our own trapping efforts.

We have learned a lot about bears in Maine over the last 35 years, but we are still discovering new things. Each field season of data collection still reveals unexpected surprises. The Department's bear monitoring program is an ongoing source of information providing biologists with the information necessary to properly manage this valuable wildlife resource. It is "our finger on the pulse of the bear population".

This work is possible thanks to a federal tax on firearms, ammunition and other hunting related items. The funds from this federal tax (known as Pittman-Robertson funds) pay for about 75% of the cost of the program. The remaining 25% comes primarily from hunting and fishing license sales.

Sick, Injured Bears or Orphaned Cubs

Bears are sometimes injured or killed in vehicle collisions. Please report any sick or injured bears or orphaned cubs to your local Game Warden or Regional Wildlife Biologist. They will assess whether the bears in question can be captured and rehabilitated at a private rehabilitation facility. Do not try to capture these bears by yourself.