Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Species Information → Birds → Raptors → Golden Eagles → Golden Eagle Study

Maine Golden Eagle Study

Documenting golden eagle presence, habitat use, and movements in Maine through community science.

Trail camera photo of a golden eagle at a bait site.

Photo by Albert Ladd

On this page:

- About the Study

- Ways to Participate

- Background

- Golden Eagle Identification

- Study Updates

- Additional Resources

About the Study

Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife in collaboration with the Eastern Golden Eagle Working Group (EGEWG) and Conservation Science Global (CSG) is working to better understand golden eagles in Maine, and we need your help!

The golden eagle is an Endangered species in Maine and is of concern throughout its eastern range due to its small population size, vulnerability to human-related threats, and considerable gaps in knowledge about habitat use and movement. This project aims to address these knowledge gaps to inform management actions by raising awareness of golden eagles in Maine and increasing participation in conservation efforts through community science. The focus of this project is the use of trail cameras to detect the presence of golden eagles, but there are several ways for birders, hunters, landowners, trappers, and wildlife enthusiasts to participate!

Ways to Participate

- Monitor a Baited Camera Trap

- Provide a Camera Trap Site

- Provide Lead-Free Bait

- Report Observations of Golden Eagles

- Help Spread the Word

Monitor a Baited Camera Trap

Photo by Chris Martin

Baited camera traps are motion-activated trail cameras set up to photograph visitors to a supplied food source. They are an effective way to detect golden eagles that often would not otherwise be observed. Managing a camera trap is the best way to be involved in the full scope of this project and creates an excellent opportunity to learn about golden eagles as well as other wildlife along the way. Anyone who currently monitors baited camera traps, such as hunters or photographers, is welcome to join. Additionally, those interested in trying it for the first time or collaborating with friends, family, organizations, or school groups are encouraged to participate!

What you'll do:

- Set up and bait a camera trap.

- Monitor the camera battery level and regularly check the camera positioning and settings

- Manage the bait supply by reviewing the most recent photos or through a site visit.

- Add bait as necessary to maintain a continuous supply if monitoring a site during January and February.

- Add bait once per month that you expect would last about a week if monitoring a site between April and December.

- Submit all photos that were taken regardless if eagles were present.

Camera Trap Quick Start Guide (PDF)

Carefully review the complete detailed Golden Eagle Study Camera Trap Protocol (PDF) before establishing a site and/or joining the study.

What you'll need:

-

Trail Camera

You'll need a reliable trail camera that is set to take photos in response to motion with a minimum interval of 1 minute. You will also need batteries, such as lithium batteries that are more effective in cold weather.

-

Bait

Deer carcasses work well for eagles, but any type of animal will do. If you are getting lots of eagles, ravens, and other scavengers, you may need many carcasses throughout the study period; the exact number you need will be determined by how quickly they disappear and how long you monitor a site.

All carcasses should be lead-free (i.e., not harvested or dispatched with lead ammunition). When eagles accidentally eat lead fragments as they consume carrion, the lead is absorbed in their blood, tissue, and bones and can be fatal. Eagles and other avian scavengers are particularly susceptible due to the high acidity in their stomachs which break down the lead fragments, exposing them to potentially toxic levels of lead.

Learn more about how choosing non-lead ammunition benefits eagles (PDF)

Options for Obtaining Lead-Free Bait- Get in touch with nearby slaughter and meat processing facilities to ask if they have renderings that are from animals that were harvested without the use of lead ammunition or chemical euthanasia (e.g., barbiturates). Lists of potential facilities can be found here or here.

- Reach out to a local trapper for potential opportunities for lead-free carcasses. Consider joining Facebook groups such as Maine Trappers Association, and Maine Fur Trappers. Beavers may work well.

- Request to be contacted about opportunities to collect roadkill in your area by getting in touch with your nearest Maine Warden Service dispatch center, local law enforcement, or MDOT Regional office. Feel free to provide contact information for the Golden Eagle Study if that is helpful.

- Collect roadkill items yourself by contacting Maine State Police who will connect you with a game warden who can provide permission if appropriate by issuing a possession permit number.

- If you need help finding additional sources of bait, email MDIFW Raptor Biologist Erynn Call at erynn.call@maine.gov for potential resources or connections with other project participants.

-

Land

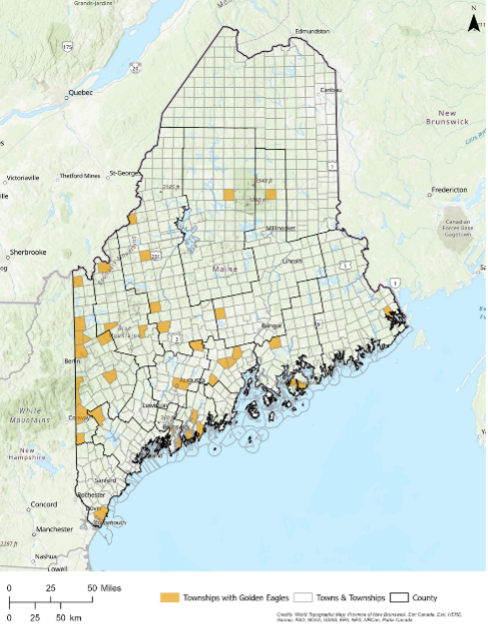

To attract and photograph golden eagles, you need to locate a suitable accessible site. Keep in mind that it is required by law to obtain written permission (e.g., via email, text, or paper) before setting up a baited game camera site on any property that is not your own. View the map below to see historic breeding regions and areas with documented golden eagle observations. Camera traps in these areas are of particular interest but sites outside of these areas are still of great value.

Figure 1a. Maine golden eagle observations

2013 – 2023 and historic breeding regions.

Map courtesy of Trish Miller, Conservation

Science Global. Observations and

documented breeding are intentionally

not distinguished on this map to

help keep the nesting areas private.

View maps of historic breeding regions and observations by county

The site should have suitable habitat for golden eagles, particularly in isolated forested areas or hilltops. The following are attributes of sites that are suitable for this project and for attracting and photographing golden eagles:

- Accessibility

The site will need to be accessed every 2-5 days (depending on how long the bait lasts and what type of game camera you use). Drive-in sites that are safe to access year-round are best. - Small clearings

Eastern Golden Eagles seem to prefer small clearings - smaller than you'd expect. Even a 30–60-foot diameter is suitable, but a 500-foot diameter is probably too large. - Large Trees

Goldens prefer to perch in large trees near a carcass and watch it for a while before coming in, so it's good if there are a few big trees 10-30 feet from the bait site. - Elevation

Golden eagles come in more readily to areas that are higher than the surrounding area and seem less willing to visit low-lying areas. If a low-lying area is your only choice, give it a try!

- Accessibility

If this project sounds like a good fit for you, fill out the following form to sign up and get started. If you would like to participate but do not have access to a suitable site, please indicate on the form that you would like to connect with a landowner if one is participating in the project in your area.

Don't forget to carefully review the complete detailed Golden Eagle Study Camera Trap Protocol (PDF) before establishing a site and/or joining the study.

Contact Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Raptor Biologist, Erynn Call, at erynn.call@maine.gov with any questions.

Provide Non-Lead Bait

Photo by Laura Zamfirescu

Providing lead-free bait for a camera trap site is a great way to help volunteers successfully maintain and monitor a location.

Anyone can contribute, but it is a particularly good fit for trappers who harvest or dispatch animals without the use of lead ammunition and who are interested in a unique opportunity to get involved in endangered species conservation.

Bait may include renderings from slaughter and meat processing facilities, roadkill (with appropriate permission/permits), or legally harvested animals. Deer carcasses work well for eagles, but any animal the size of a beaver or larger will do. We try to avoid using predators (coyotes, foxes) as it may scare away the eagles and not use any birds due to concern with spreading Avian Influenza.

All carcasses must be lead-free (i.e., not harvested or dispatched with lead ammunition). When eagles accidently eat lead fragments as they consume carrion, the lead is absorbed in their blood, tissue, and bones and can be fatal. Eagles and other avian scavengers are particularly susceptible due to the high acidity in their stomachs which break down the lead fragments, exposing them to potentially toxic levels of lead.

Learn more about how choosing lead-free ammunition benefits eagles (PDF)

Fill out the form below to have your contact information added to a list of potential bait sources for project participants. If connected with a site monitor, you can coordinate with them directly to donate your bait.

Contact Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Raptor Biologist, Erynn Call, at erynn.call@maine.gov with any questions.

Report Observations of Golden Eagles

Juvenile golden eagle photo by Elisa Dahlberg

If getting involved with baited camera traps isn't a good fit for you, you can also contribute to the project by reporting golden eagle sightings. With this option, there is no need to sign up. Simply report the date and location of any golden eagle sightings in Maine. There are two options for reporting golden eagles:

- The best way to report golden eagle sightings is through eBird. Create a free account and get started today!

- Sightings may also be reported on the MAINE Birds Facebook group.

Be sure to brush up on your eagle identification skills before you get started. Bald eagles and golden eagles are both native Maine species, but golden eagles are rare and elusive, and their distribution is not well understood. Learning to confidently distinguish the two is an important first step in contributing to eagle conservation as a community scientist.

You might think that the bright white head of a bald eagle makes this a simple task, but it takes our nation's symbol five years to develop their iconic plumage. For this reason, juvenile bald eagles are often mistakenly identified as golden eagles. Take a look at some key similarities and differences that will help you become proficient in Maine Eagle Identification.

Help Spread the Word

For this project to be successful, we'll need as many people as possible to participate from different areas of the state. One of the best ways you can help is to spread the word about this exciting community science opportunity! Share a link to this page (mefishwildlife.com/goldeneaglestudy) on your social media pages, and/or download and share the project flier:

Background

Photo by Don Dunbar

The eastern population of golden eagles is genetically distinct from its western counterpart, breeds in a region that extends from Manitoba eastward to Labrador and spends winters east of the Great Plains. This population is of concern throughout its range. Golden eagles are listed as Endangered under the Maine Endangered Species Act and a Species of Greatest Conservation Need within the state Wildlife Action Plan.

The last known pair of breeding golden eagles disappeared from the state in 1997, but Maine serves as a migratory corridor and hosts goldens that reside in the state in the summer and winter. Eagles tracked with telemetry have visited areas near historic nests during summer, suggesting that these sites could host breeding eagles in the future. However, the extent of use in the summer, as well as the distribution, habitat use, and movements of eagles throughout the year remains largely unknown.

By harnessing the collaborative efforts of community science, our goal is to enhance our understanding of the presence and movements of Goldens in Maine and beyond. This knowledge will enable us to make well-informed management decisions.

In addition, if a golden eagle is regularly detected by a camera trap, it creates an opportunity for biologists to capture the bird, collect biological samples, and affix a transmitter so their movements can be tracked using telemetry.

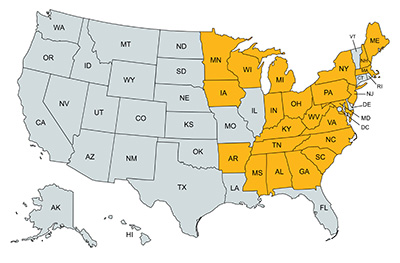

Maine is just one of several states with similar research efforts focused on better

understanding golden eagle populations in the eastern United States.

The Maine Golden Eagle Study is part of a large-scale regional effort to better understand golden eagle abundance, distribution, movements, and habitat use in eastern North America. Numerous federal and state agencies, non-profit research organizations, and universities are conducting similar studies, and are working collaboratively to reach golden eagle conservation goals. We are proud that Maine is a part of this effort, and excited that you, our state's community scientists, can participate!

Golden Eagle Identification

Learning to confidently distinguish Maine's two native eagle species, bald eagles, and golden eagles, is an important first step in contributing to eagle conservation as a community scientist.

Golden eagle, photo by Randy Flament

Juvenile bald eagle, photo by Deb Powers

Adult bald eagles, photo by Laura Zamfirescu

You might think that the bright white head of a bald eagle makes this a simple task, but it takes our nation's symbol five years to develop their iconic plumage. For this reason, juvenile bald eagles are often mistakenly identified as golden eagles. Below are a few key similarities and differences to help you become proficient in eagle identification:

- Golden eagles and bald eagles are about the same size. They are approximately 2.5 feet tall with a wingspan of about 6.5 feet, and weigh about ten pounds on average.

- Golden eagles have feathers all the way down to their feet but bald eagles do not.

- Adult golden eagles have amber highlights on their head and neck. Adult bald eagles have a sharply contrasted white head and tail.

- Immature golden eagles have a white tail band and distinct white patches on the bottom side of their wings. Immature bald eagles have mottled white highlights.

Golden eagle, photo by Tricia Miller

Bald eagle, photo by Tricia Miller

Juvenile golden eagle, photo by Elisa Dahlberg

Juvenile bald eagle, photo by Benjamin Hack

Learn more about Maine Eagle Identification (PDF)

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology's All About Birds page is also a fantastic resource.

Photo by Randy Flament

Distinguishing similar species in trail camera images is tough because most images will not be perfectly clear like illustrations and photographs in field guides. Key features may not always be visible in the images you capture. If you are going to monitor a camera trap site for this project, it's a good idea to study camera trap images of golden eagles in addition to using a guide. Practicing your identification skills in this context will help you build confidence in identifying golden eagles in various life stages in your own camera trap images.

Study Updates

Fall 2024 Study Update

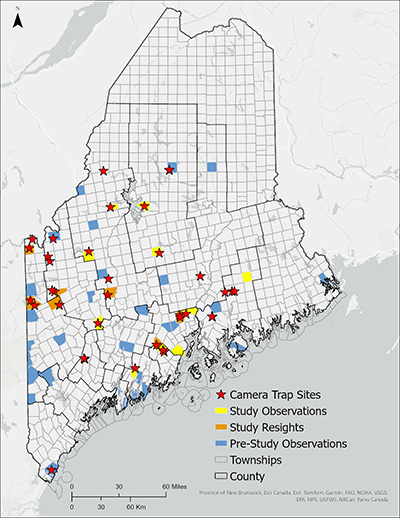

Before the start of the study, golden eagles had been documented in 31 townships across 39 unique sites over the past decade. These sightings represent the baseline, or pre-study, observations.

Since the study began in January 2024, observations have been recorded in 20 townships. Nine of these townships overlap with pre-study observations, while 11 represent new areas where golden eagles were observed for the first time.

Across both pre-study and current study periods, no golden eagle sightings occurred from May through September. This gap is likely due to the limited use or sharing of baited camera trap photos during these months.

Observations from 22 sites within 20 townships documented golden eagle presence on 99 days. The most frequently visited site recorded golden eagle presence for 26 days, followed by another site with 14 days. Five additional sites had golden eagle activity ranging from six to nine days, and the remaining sites ranged from one to three days.

Of the 99 observation days in 2024, 95 were captured via baited trail cameras, three through eBird reports from birders, and one by a camera trapper who photographed a golden eagle flying away by chance with a cell phone. Baited trail cameras have proven highly effective for detecting golden eagles; it's rare to spot them without this method.

Since the study launched, observations confirming golden eagle presence were submitted as follows: 2024 (13 sites), 2023 (6 sites), 2020 (1 site), 2018 (2 sites), 2016 (1 site), and 2015 (1 site).

Approximately 45 camera trap sites submitted photos in 2024, and 13 of these sites documented golden eagle activity.

For study outreach, information has been shared through multiple formats, including email and social media. A presentation on the study was given at the 2024 Raptor Research Foundation conference.