Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Species Information → Birds → Raptors → Bald Eagles

Bald Eagles

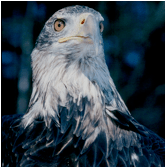

Identification: Our national symbol is highly recognizable. However, some observers do not realize their different appearance in the first 3 – 4 years. Immature eagles are generally dark with varying degrees of lighter mottling. They are full grown when fledged at 3 months of age. At 5 years of age, a (sexually mature) adult bald eagle has a pure white head and white tail that sharply contrast the dark brown feathering elsewhere on the body. In flight, notice the relatively long head / neck profile (about 50% of the length of the tail) unlike smaller proportions on a golden eagle silhouette.

© Paul Cyr, Crown of Maine Photography

© Betsy Marcello

If you see an immature eagle, several head features allow ageing. First-year juveniles are dark colored especially on head feathers, beak color, and iris color. A second-year bird has buffy areas on its head and throat. By the third-year, head feathers are whitish except for a conspicuous dark eye stripe; also, the beak color and iris are yellowing.

© Paul Cyr, Crown of Maine Photography

© Charlie Todd, MDIFW

Natural history briefs: Bald eagles are creatures of habit. What seems “the same eagle perched on the same limb of the same tree” may be a series of individuals over time. They are selective about food sources, perches, nocturnal roosts, and especially nests.

Typical perches of bald eagles,

Aroostook County

© Paul Cyr, Crown of Maine Photography

Maine’s bald eagles are primarily fish eaters at inland settings on the lakes and rivers. In coastal estuaries and (especially) offshore, they eat a more varied diet adding seabirds and waterfowl. Eagles will perch along shorelines waiting for prey. Hunting flights are usually extended glides low over open water: trying to stay dry while catching a meal on the wing. If they get too wet, they will use their wings like oars and remain on the shore or a very low perch in order to dry out before attempting to fly again.

Although some leave the state, many bald eagles remain through the winter in Maine. Scavenging carrion becomes more prevalent as ice cover greatly limits food availability.

Conservation: Stewardship of bald eagle nesting habitat by landowners has been solicited since 1972 in Maine. From 1980 to 2009, MDIFW applied Essential Habitat rules at eagle nests under the Maine Endangered Species Act. Land purchases and conservation easements now provide a lasting safety net for → 400 eagle territories to safeguard recovery. An array of conservation organizations is integral to this strategy.

Site fidelity by nesting eagles over time, Penobscot County

© Sharon Fiedler

Generations of bald eagles will use the same nesting territory sequentially over decades. In fact, the same nest is often reused if its ever enlarging size does not harm the tree. A Sagadahoc County nest found in 1963 measured 20 feet vertically; biologists conservatively estimated it had been in use for at least 60 years.

National management guidelines (PDF) have been adopted to minimize disturbances of nesting eagles under the authority of a federal law, the Bald Eagle – Golden Eagle Protection Act. These are now the primary legal standard applicable to bald eagle nests in Maine.

Bald Eagle Recovery

Photo by Sharon Fiedler

This interactive Story Map documents the recovery of the Bald Eagle in Maine from 1962-present. Learn about the methods used by the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife to assist the recovery of the eagle population, including egg transplants, habitat management and conservation, co-operative agreements to protect nests and Essential Habitats. The story also highlights various fun topics of interest such as Maine's oldest eagle, radio-tracking eagles, Maine's largest nest, and so on.