DACF Home → Bureaus & Programs → Maine Forest Service → About Us → Forest Health & Monitoring → Invasive Threats to Maine's Forests and Trees

Invasive Threats to Maine's Forests and Trees

Wood Borers: These insects' worm-like larvae develop beneath the bark or within the wood leaving tunnels as evidence; emerging adults leave holes in the bark.

Piercing-Sucking Insects: These insects feed on fluids of the host plant. Many spend a significant part of their lives attached to the host plant.

Defoliators: These insects consume the foliage of host plants. The two featured here do their damage as larvae.

Diseases: The disease featured here had devastating effects in parts of the Western United States and has a broad host range.

Asian Longhorned Beetle

Origin: Asia

Hosts: Hardwood trees, especially maples.

Status in Maine: Not known to be present

**This insect can be spread on firewood. Please leave your firewood at home.**

Nearest Known Occurrences: The Asian longhorned beetle has been detected in Worcester and Boston Massachusetts (More Information). New York City area in New York and adjacent areas in New Jersey.

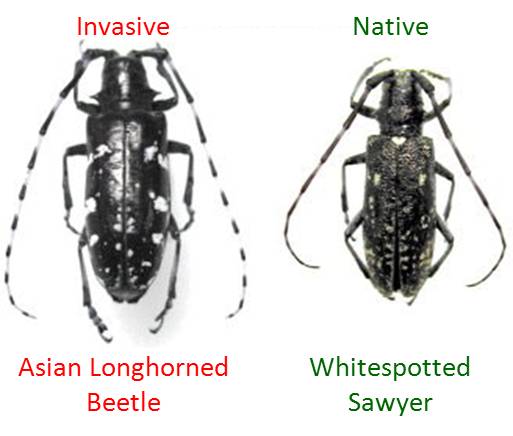

Description: Glossy black (think patent leather), very smooth beetle with white spots on the wings. Antennae are at least the length of the body and banded with black and white (how to tell Asian longhorned beetle from whitespotted sawyer).

Signs and Symptoms: Oval to round wounds on the bark where the females have chewed out a site to deposit their eggs. Round emergence holes in the trunks and branches of trees. Piles of coarse sawdust at the base of trees.(For images and more detailed descriptions, see DACF, Maine Bug Watch’s Damage Page)

Damage: Tunneling by larvae girdles tree stems and branches. This leads to dieback of the tree crown and eventual death of the tree. (Images of Asian longhorned beetle damage in trees)

- Division of Animal and Plant Health

- The Nature Conservancy Video: Worcester, MA landscapes before and after tree removal (Quicktime | 812 KB, new window will open).

- US Forest Service Site

- USDA APHIS Site

- University of Vermont Entomology Lab Site

- Canadian Training Guide

Brown Spruce Longhorn Beetle

Brown Spruce Longhorn Beetle

Origin: Europe

Hosts: Spruce (usually), Fir, Pine, Larch (secondary), Hardwoods (rare)

Status in Maine: Not known to be present

Nearest Known Occurrences: Nova Scotia, Canada.

Description: Flattened brown beetle, very similar to native long-horned beetles. Reddish-brown antennae ½ length of body.

Signs and Symptoms: Crown decline. Oval to round holes in bark, resin streams down the stem. Coarse sawdust at the base of the tree, on the stem and/or packed into the holes. Flattened, meandering larval feeding tunnels under the bark. L-shaped pupation chamber in the sapwood.

Damage: This beetle generally attacks unhealthy trees in its native environment. In Nova Scotia it has been found to attack and kill healthy trees.

MORE...

Emerald Ash Borer

Origin: Asia

**Many new infestations center around campgrounds, implicating camp firewood in this insect’s spread**

Hosts: Ash

Status in Maine: Established

Nearest Known Occurrences: Maine; Edmundston, NB; New Hampshire, Northeastern Massachusetts (Where else is EAB?).

Description: Metallic green beetle with wings and body tapered towards the rear.

Signs and Symptoms: Symptoms and signs include D-shaped adult exit holes, bark splitting, serpentine frass-filled (sawdust-like waste) feeding galleries, wood pecker feeding, crown dieback, and epicormic shoots (whips growing off the trunk and branches). Many of these symptoms and signs are similar to other insects and diseases of ash. Is it EAB?

Damage: Larval feeding under the bark girdles and kills ash trees. Since its discovery in the United States in 2002 emerald ash borer has killed millions of ash trees.

Biosurveillance: Biosurveillance uses one living organism to monitor for another. A native non-stinging wasp, Cerceris fumipennis, is a efficient survey tool for detecting emerald ash borer.

Purple Traps: Large, purple, sticky traps are hung in ash trees to help look for the emerald ash borer.

Sign up to be notified of upcoming Emerald Ash Borer Updates for Municipalities webinars

MORE...

- How to Create a Trap Tree to Monitor for Emerald Ash Borer

- Basket Trees (PDF | 550 KB) Maine Forest Service/Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance poster)

- USDA APHIS site

- Emerald Ash Borer Information Network (Information from Across the US and Canada)

Elongate Hemlock Scale

Origin: Japan

Hosts: Hemlock, spruce, fir = primary hosts. Secondary coniferous hosts only usually infested in the presence of heavy scale populations on primary hosts.

Status in Maine: Established

Nearest Known Occurrences: To date EHS has been found on planted hemlocks in southern Maine and in the forest in Kittery Point, ME.

Description: A member of the armored scale insects, females are covered by a smooth, yellow-brown parallel-sided waxy covering, males by an white, elongate covering. Size ranges from 0.1mm to 2mm.

Signs and Symptoms: Mottled, yellowing needles, thinning foliage. Coverings of females and males (described above) and thread-like floss. Where to look: Planted hemlock, spruce and fir. Planted and natural hemlock in areas affected by hemlock woolly adelgid.

Damage: Needle mortality, crown thinning, tree decline and mortality. Branch dieback, as in hemlock woolly adelgid starts in the bottom branches of the crown. Decline may be more rapid in the presence of hemlock woolly adelgid (described above)

MORE...

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

Origin: Japan

Hosts: Hemlocks

Status in Maine: Established

Nearest Known Occurrences: Hemlock woolly adelgid is known to be established in many areas in southern and coastal Maine from Kittery to Mount Desert Island, with higher populations in south-western coastal areas and more scattered populations in eastern and inland areas.

Description: Hemlock woolly adelgid is a small, aphid-like insect covered with white, waxy wool-like material. This covering makes the insect resemble miniature cotton balls. It is most visible from late-October through July. Wool masses are located on the undersides of the twigs at the bases of the needles (not on the needle, but on the twig).

Signs and Symptoms: The white waxy cotton ball-like covering of this adelgid is the most obvious sign of this insect.

Damage: Feeding by the adelgid leads to needle loss, crown thinning and dieback and eventual mortality of trees. Decline may be more rapid in the presence of elongate hemlock scale (described below).

Seasons: Due to the life-cycle of hemlock woolly adelgid, work should be conducted in hemlock in late-summer through winter. During this period, the adelgid is least likely to be in egg and crawler forms. A single egg or crawler can start a new population of hemlock woolly adelgid.

Rules: There is a quarantine on hemlock woolly adelgid which also affects movement of hemlock branches and top material as well as rooted hemlock.

MORE...

Red Pine Scale

Origin: Japan

Hosts: Red pine scale is known to infest red pine (Pinus resinosa), Japanese red pine (P. densiflora), Japanese black pine (P. thunbergii) and Chinese pine (P tabulaeformis).

Status in Maine: Established

Nearest Known Occurrences: Red pine scale was detected in Mount Desert, Hancock County, Maine in September 2014. This was the first known occurrence in Maine, it has since been found in Washington and York Counties. Red pine scale is found throughout New England, New York, New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania.

Description: Red pine scale is one of the Matsucoccus scales, a soft scale. Most recognizable stages of the insect are covered in white, waxy, wool like material. The sub-adult males spin capsule-shaped, loosely woven cocoons which can be found on the branches of affected trees. The females create wispy, woolly ovisacs. When the immature insect is settled on the tree it resembles a smooth, waxy pod, lacking antennae and legs, but adorned with sparse tufts of wool.

Description: Red pine scale is one of the Matsucoccus scales, a soft scale. Most recognizable stages of the insect are covered in white, waxy, wool like material. The sub-adult males spin capsule-shaped, loosely woven cocoons which can be found on the branches of affected trees. The females create wispy, woolly ovisacs. When the immature insect is settled on the tree it resembles a smooth, waxy pod, lacking antennae and legs, but adorned with sparse tufts of wool.

Signs and Symptoms: Off-colored needles progressing from olive-green, to yellow, to red—first on individual branches, then whole trees. White wool-covered insects (as described above).

Damage: needle, branch and whole tree mortality.

Maine Forest Service Red Pine Scale Fact Sheet (PDF)

Beech Leaf Mining Weevil

Beech leaf mining weevil larval damage

Beech leaf mining weevil larval damage

(Photo credit: NRCan)

(Photo credit: NRCan)

Origin: Europe

Hosts: In North America, only beech species are affected.

Status in Maine: Not established

Known Occurrences: Beech leaf mining weevil is not known to occur in Maine. It is however currently established in Nova Scotia, centered around the greater Halifax area.

(Photo credit: J. Sweeney)

Description: Adults are small black beetles, approximately 2.5 mm long. Larvae are approximately 5 mm long and are pale white with a black head.

Signs and Symptoms: Two types of damage can occur on leaves of beech and may be seen at the same time. Adults emerge from overwintering and will free feed, creating a “shot-hole” pattern across the leaf surface. The more distinctive type of damage is caused by larvae mining the internal tissues of the leaf. Mines will begin as a narrow channel at the center leaf vein, expanding outwards towards the outer margin into a larger brown blotch. Brown mined portions may later fall away, giving the leaf a tattered appearance.

Damage: Defoliation leads to reduced photosynthetic ability and reduced growth, which may eventually result in tree death. Mortality of beech in Nova Scotia appears to occur after 5-7 years of repeated defoliation.

Further research is needed to determine detrimental interactions of beech leaf mining weevil and beech leaf disease. The presence of beech bark disease appears to have a minimal effect on mortality due to beech leaf mining weevil.

Browntail Moth

Origin: Europe

Hosts: Hardwoods (oak, shadbush, apple, cherry, beach plum, and rugosa rose)

Status in Maine: Established

Nearest Known Occurrences: Browntail moth is known to be established in Southern and Coastal Maine and Cape Cod Massachusetts.

Description: Large larvae, about 1 1/2 inches long, are dark brown and have a broken white stripe on each side of the body and conspicuous, unpaired, reddish spots on the posterior end of the back. is dark brown and hairy, with parallel white markings running down the back. Reddish spots will be apparent in early instars as well.

Signs and Symptoms: Feeding by the browntail moth will vary with the season. Larvae overwinter, so feeding begins early in the spring, damage is visible as the leaves unfurl. As the larvae grow the consume larger and larger chunks of the leaves, and can completely defoliate host trees. Affected trees usually refoliate within the same season. After the overwintering larvae hatch in the summer, they will skeletonize leaves, and tie them with silk to the host branches. Winter webs on the outside edges of host crowns are conspicuous, tightly woven clusters of skeletonized leaves silk and sometimes fruit, filled with tiny larvae and frass. Winter web abundance can be a good barometer of summer suffering.

Damage: Although browntail moth is a forest pest, and can cause mortality of host trees, the biggest impacts are on human health and economics. Exposure to irritating hairs can cause a wide range of symptoms, from mild to very severe. See our Fact Sheet for more information.

Elm Zigzag Sawfly

Origin: East Asia

Hosts: Elms (Ulmus spp.)

Status in Maine: Not known to be present.

Known Occurrences: Elm zigzag sawfly’s first North American confirmation occurred in 2020 in the Canadian province of Quebec, and has since spread to other provinces including New Brunswick, and southeast Ontario. In the United States, it is now found in many states including Vermont and Massachusetts in New England.

Description: Larvae are light green and grow from 1.8 mm up to 11 mm when fully mature. Like other sawflies, they have more than 5 sets of prolegs along the abdomen in addition to their forward sets of true legs, which can be used to distinguish them from caterpillars. Larvae have a dark “T” shaped mark above the second and third sets of true legs, as well as a dark lateral band on the head. Adults are shiny, black, and resemble small wasps (6-7 mm), though they do not have a narrowed waist nor stinger.

Signs and Symptoms: True to its name, larvae feed on leaves in a distinctive zigzag pattern. Once larvae become large enough however, zigzagging may become less apparent as they begin feeding on the entire leaf, often leaving behind only the larger leaf veins.

Damage: While elm mortality hasn’t yet been observed in the U.S. due to elm zigzag sawfly, defoliation can predispose elms to diseases and other stressors. In some cases, the entire crown of the tree can be defoliated once a population is large enough and the death of individual branches has been observed.

- Canadian Invasive Species Centre – Elm zigzag sawfly

- Elm zigzag sawfly (nrcan.gc.ca)

- UMass Amherst – Elm zigzag sawfly

Winter Moth

Origin: Europe

Hosts: Primarily hardwoods (Oaks, Maples, Ashes, Cherries, Apple, Blueberries)

Status in Maine: Established

Known Occurrences: Winter moth is known to be established in Coastal Maine From Kittery to Bar Harbor. Defoliation by this pest was first noted in May 2012.

Signs and Symptoms: Feeding by the winter moth caterpillars begins before buds burst in the spring. Early feeding damage to expanding leaves can be damaged to the point that they look like swiss cheese. Later in the season trees in areas with heavy infestations can be completely stripped of foliage. Caterpillars are present from before the leaves emerge to mid June. (Photo guide to damage, PDF | 3.3 MB)

Signs and Symptoms: Feeding by the winter moth caterpillars begins before buds burst in the spring. Early feeding damage to expanding leaves can be damaged to the point that they look like swiss cheese. Later in the season trees in areas with heavy infestations can be completely stripped of foliage. Caterpillars are present from before the leaves emerge to mid June. (Photo guide to damage, PDF | 3.3 MB)

Damage: Defoliation leads to loss of capacity to produce energy. Severe defoliation over several years can cause tree mortality, as has been the case in Massachusetts in recent years.

Human Aided Spread: Winter moth caterpillars pupate in the ground and can be moved in soil from late May through December. During this time period moving plant material associated with soil is not recommended. Caterpillars can also be accidentally spread on and in cars, boats and other conveyances.

Biocontrol program: A parasitoid fly called Cyzenis albicans has proven to be an effective biocontrol agent against winter moth in other parts of New England. The fly is very host specific with little to no non target effects. We have been releasing C. albicans in Maine since 2013 with a list of release sites including Harpswell, Cape Elizabeth, Kittery, South Portland, Vinalhaven, Portland, Bath, Boothbay harbor and East Boothbay Harbor.In it’s native range in Europe winter moth caterpillars are an important food source for migrants and birds gearing up for nesting season since it is one of the first caterpillars available in the spring. Fortunately here in the northeast, birds have begun to key into this food resource and give some supplemental control.

- Maine Forest Service Winter Moth Fact Sheet

- Where in Maine might I expect defoliation by winter moth?

- US Forest Service Pest Alert

- Massachusetts Introduced Pest Outreach Project Winter Moth FAQ

- Massachusetts DCR Pest Alert

Beech Leaf Disease (BLD)

Origin: Unconfirmed

Hosts: All beech trees are susceptible to BLD, including European and Asian species (this includes beech cultivars available in the nursery trade).

Status in Maine: Established

Nearest Known Occurrences: BLD was first detected in Maine in Lincolnville (Waldo County) in 2021. Symptoms of the disease have also been seen in other Maine counties. The exact extent of the disease is unknown, and may be widespread. BLD was first recorded in Ohio in 2012.

Description: A microscopic roundworm (the nematode, Litylenchus crenatae) has been consistently associated with symptoms, but the role of the nematode and other microorganisms in the proposed disease complex is not fully understood. Mature beech can be significantly stressed by BLD, and in some cases killed. Impacts to understory beech can be severe, leading to tree death in 3 to 5 years. The interaction of BLD and beech bark disease may hasten beech tree decline.

Signs and Symptoms: BLD symptoms include dark-green striped bands between lateral leaf veins, reduced leaf size, leaf curling and premature leaf drop. The banded areas of leaves may be leathery in more advanced infections. As the disease progresses, buds are aborted in greater numbers leading to reduced canopy and tree death. Larger trees take longer to succumb to BLD.

Damage: This disease has caused extensive mortality of understory beech trees wherever it has become established. Beech is a common tree species in Maine with high ecological importance, already compromised by the beech bark disease complex.

MORE...

Oak Wilt Disease

Origin: Unconfirmed

Hosts: Oaks; symptoms are severe and end in mortality on species in the red oak group (oaks with pointed leaf tips). Species in the white oak group (oaks with rounded leaf tips) are also susceptible but decline more slowly.

Status in Maine: Not known to be present

Nearest Known Occurrences: Tree damage and mortality by the causal fungus, Bretziella fagacearum, has been confirmed in three locations on Long Island, New York, one location in eastern and one in western New York State. Oak wilt has not been detected in Maine.

Description: The disease causes wilting symptoms leading to mortality and is vectored (spread) by sap-feeding beetles that are attracted to wound areas on trees. The beetles can carry spores from infected oaks to recently wounded oak trees. Once oak wilt is established in a stand of oak trees, it can spread below ground through tree root grafts (junctions where adjacent trees join their root systems) creating pockets of oak mortality.

Signs and Symptoms: The oak wilt fungus kills the xylem tissues in the inner bark leading to wilting and killing of branches (flagging). As the disease progresses in the tree, wilting and branch mortality expands with trees dying in the same year or the next year, depending on timing and mode of transmission. When the disease is spread through the roots, the entire tree will die rapidly. The disease persists for several years in white oak species, causing noticeable but less-severe symptoms and an overall slower tree decline. White oaks can serve as a reservoir of oak wilt disease.

Damage: This disease has caused mortality of oaks in the Midwestern United States for decades and is a threat to oaks in natural and residential areas. Damage to oak trees via pruning or otherwise from April to October should be strictly avoided in areas where the oak wilt pathogen is present. This is because the insect vectors of the fungus spread the disease from infected trees to wounds on otherwise healthy trees. If oak trees are wounded during this time or must be pruned, a wound dressing or latex paint should be thoroughly applied to avoid attracting the beetle vectors.

- Oak Wilt Disease Information Sheet (PDF | 727 KB)

- US Forest Service information on oak wilt

- Towards Early Detection of Oak Wilt in Maine_Lessons Learned from Oak Wilt Training in Minnesota and Wisconsin 2019 (PDF | 4.02 MB)

- Oak wilt information and videos from the State of New York

Sudden Oak Death

Origin: Unknown

Hosts: Numerous (see list on APHIS site)

Status in Maine: Not known to be present

Nearest Known Occurrences: Canker damage occurs in California and Oregon. The disease causing organism, Phytophthora ramorum, was found on one potted lilac plant in Maine, but it is not believed to be established in Maine. Surveys of four forested watersheds in central and southern Maine were conducted during 2007, with no P. ramorum found at any location.

Description: The causal agent of sudden oak death is a fungus-like micro-organism called Phytophthora ramorum. Laboratory tests are necessary to confirm this species as the cause of disease.

Signs and Symptoms: P. ramorum causes two types of symptoms. In "bark canker" hosts, such as oaks, large cankers can be found on the trunk or main stem. Crown browning will also occur. In "foliar hosts", leaf blight (gray to brown lesions) and twig dieback may be found.

Damage: This disease has caused mortality of oaks and tanoaks in parts of the western United States (bark canker hosts). Foliar hosts may serve as a reservoir for disease inoculum.