DHHS → MeCDC → Disease Surveillance → Epidemiology → Vectorborne → Tick Messaging → Tick Prevention and Property Management

Tick Prevention and Property Management

Reducing your exposure to ticks lowers your chances of getting a tickborne disease. While it is good to take preventative measures against ticks all year, you should be extra careful during warmer months when ticks are most active. If you work or play outdoors, you should:

- Wear EPA-approved repellents.

- Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of trails.

- Wear long-sleeved, light-colored clothing.

- Tuck your pant legs into your socks and your shirt into your pants.

- Check your clothing and gear for ticks and do a full-body tick check when coming back indoors. Pay special attention to under the arms, behind the knees, between the legs, in and around the ears, in the belly button, around the waist, and in the hair.[1]

- Take a shower within two hours after spending time outdoors, which will wash off any unattached ticks.[1]

What types of repellents should I use to prevent ticks?

- Use repellents that contain 20% DEET or greater to effectively repel ticks for several hours.[2],[3] Other EPA-approved tick repellents for use on skin include picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus, and IR3535.[4],[5],[6]

- Products containing permethrin can treat clothing/gear and last for several washes.[5] Permethrin treated clothing is shown to be highly effective at preventing tick bites.[7]

- In general, products containing natural ingredients tend to be less effective at repelling ticks than other EPA-approved repellents.[5],[6],[7]

- You should always follow the instructions on the label.

What should I do after returning from a tick habitat?

- Ticks can be very small and are hard to see. After being outdoors be sure to check your clothing and gear and conduct a full-body tick check by looking and feeling for ticks.

- Ticks can attach anywhere on the body, so it is important to check your whole body. However, ticks prefer warm, moist areas of the body. These areas include under the arms, behind the knees, between the legs, in and around the ears, in the belly button, and in the hair.[8]

- Showering within two hours of coming indoors may help wash off unattached ticks.[1],[8],[9] This also provides a good opportunity to do a tick check.

- Placing clothes directly in a dryer and drying on high heat can effectively kill ticks on clothing.[10]

What should I do if I find an attached tick?

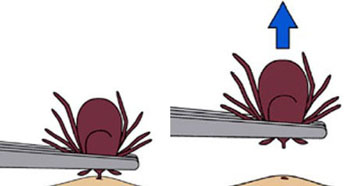

- Remove attached ticks as soon as possible. While there are many tick removal devices available, a pair of fine-tipped tweezers or a tick removal spoon work best.[11],[12]

- If you are using tweezers, grasp the tick as close to the skin's surface as possible and pull upward with steady, even pressure.

- If you are using a tick spoon, place the notch on the skin near the tick. Apply slight downward pressure while sliding the spoon forward to remove the tick.

- Do not twist or jerk the tick, as this can cause the mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin.[12]

- Do not use petroleum jelly, a hot match, dish-soap, nail polish, or other folk remedies to remove ticks. They are generally not effective and may increase the risk of infection.[13]

- After removing the tick, disinfect the bite site and wash your hands with soap and water.

How can I reduce tick habitats around my yard?[14]

- Remove leaf litter and brush from your yard.[15],[16] This will decrease the areas where ticks can hide.

- Keep your lawn mowed to 3 inches or less. This lowers the humidity at ground level making it difficult for ticks to survive.

- Create a 3-foot barrier of mulch or crushed stone around the outside of your yard. Ticks do not like to cross over dry areas.

- Do not plant invasive plants such as Japanese barberry and glossy buckthorn.[16],[17] These plants provide the perfect habitat for deer ticks. If you already have these plants in your yard, consider removing them and planting native perennials or shrubs.

- Increase sunlight by pruning the lower branches of trees or thinning out shrubs and hedges. This will cause ticks to dry out and die.

What can I do to chemically control ticks in my yard?[14]

- You should talk to a licensed commercial pesticide applicator if you want to apply pesticides to your yard. Pesticides do pose risks if improperly used.

- A single spray of pesticide product labeled for wide-area tick control, applied with appropriate volume and pressure, can be effective in controlling ticks through the summer.[18]

- A second application in the fall can kill adult ticks and help reduce tick populations the following year.[18]

- Spraying open fields and lawns is not necessary.

- Your yard is not often your only exposure to ticks and tick habitat. It is important to do daily preventative measures to avoid tick bites, like daily tick checks and wearing repellents.

What role do mice and deer play in the Lyme disease cycle?[19]

- Ticks require a blood meal to reproduce.

- Deer ticks become infected with Lyme disease (and other disease-causing agents) when they take their blood meal from infected small rodents, such as white-footed mice. This means that animals like mice are the 'reservoir' for Lyme disease. Deer ticks typically attach to rodents during the first year of their life cycle and these blood meals provide the tick with nourishment for growth.

- Deer ticks commonly feed on deer to get the nutrients needed for laying eggs. Deer do not carry Lyme disease or pass it to ticks, so deer are 'reproductive hosts' in the Lyme disease cycle.

What can I do to reduce the number of deer and rodents coming into my yard?[14]

- Use bird feeders only in the fall and winter, since bird seed attracts mice.

- Put up deer fencing to effectively control deer access to your property.[1],[20]

- Keep stonewalls and woodpiles away from the home and free of brush, high grass, weeds, and leaf litter. This will decrease potential mouse nesting sites.

- Keep your wood piles and rock walls neat and away from your home and areas where children play. Small animals like mice often make these areas their home.[21]

Additional Resources

- How to Choose Tick-Control Products (PDF)

- Find the right EPA-approved tick repellent for you

References

- Connally, N.P., Durante, A.J., Yousey-Hindes, K.M., Meek, J.I., Nelson, R.S., & Heimer, R. (2009). Peridomestic Lyme disease prevention: Results of a population-based case-control study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 201-206.

- Fradin, M.S., & Day, J.F. (2002). Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(1), 13-18.

- Lupi, E., Hatz, C., & Schlagenhauf, P. (2013). The efficacy of repellents against Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, and Ixodes spp. - a literature review. Travel Medicine and Disease Surveillance, 11(6), 374-411. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.10.005

- Katz, T.M., Miller, J.H., & Hebert, A.A. (2008). Insect repellents: Historical perspectives and new developments. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 58(5), 865-871.

- Nasci, R.S., Wirtz, R.A., & Brogdon, W.G. (2015). Protection against mosquitoes, ticks, & other arthropods. Retrieved from https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/the-pre-travel-consultation/protection-against-mosquitoes-ticks-other-arthropods

- Semmler, M., Abdel-Ghaffar, F., Al-Rasheid, K.A., & Mehlhorn, H. (2011). Comparison of the tick repellent efficacy of chemical and biological products originating from Europe and the USA. Parasitology Research, 108(4), 899-904. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2131-4

- Vaughn, M.F., Funkhouser, S.W., Lin, F.C., Fine, J., Juliano, J.J., Apperson, C.S., & Meshnick, S.R. (2014). Long-lasting permethrin impregnated uniforms: A randomized-controlled trial for tick bite prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(5), 473-480. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.008

- Maine Medical Center Research Institute Vector-borne Disease Laboratory. (n.d.) Check your whole body for ticks. Retrieved from https://www.ticksinmaine.com/tickcheck

- Han, G.S., Stromdahl, E.Y., Wong, D., & Weltman, A.C. (2014). Exposure to Borrelia burgdorferi and other tick-borne pathogens in Gettysburg National Military Park, south-central Pennsylvania, 2009. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 14(4), 227-233. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1363

- Nelson, C.A., Hayes, C.M., Markowitz, M.A., Flynn, J.J., Graham, A.C., Delorey, M.J.,…Dolan, M.C. (2016). The heat is on: Killing blacklegged ticks in residential washers and dryers to prevent tickborne disease. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, 7(5), 958-963.

- The University of Rhode Island TickEncounter Resource Center. (2005-2017). How to remove a tick. Retrieved from https://www.tickencounter.org/prevention/tick_removal

- The University of Maine Cooperative Extension: Insect Pests, Ticks and Plant Diseases. (n.d.). Tick Identification Lab – Tick Removal. Retrieved from https://extension.umaine.edu/ipm/tickid/tick-removal/

- Gammons, M. & Salam, G. (2002). Tick Removal. American Family Physician, 66(4), 643-646.

- Stafford, K. (2007). Tick management handbook: An integrated guide for homeowners, pest control operators, and public health officials for the prevention of tick-associated disease. Revised edition. The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. Retrieved from https://www.ct.gov/caes/lib/caes/documents/publications/bulletins/b1010.pdf.

- Schulze, T.L., Jordan, R.A., & Hung, R.W. (1995). Suppression of subadult Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) following removal of leaf litter. Journal of Medical Entomology, 32(5), 730-733.

- Elias, S.P., Lubelczyk, C.B., Rand, P.W., Lacombe, E.H., Holman, M.S., & Smith, R.P. (2006). Deer browse resistant exotic-invasive understory: an indicator of elevated human risk of exposure to Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in southern coastal Maine woodlands. Journal of Medical Entomology, 43(6), 1142-1152.

- Williams, S.C., Ward, J.S., Worthley, T.E., & Stafford, K.C. (2009). Managing Japanese barberry (Ranunculales: Berberidaceae) infestations reduces blacklegged tick (Acari: Ixodidae) abundance and infection prevalence with Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae). Environmental Entomology, 38(4), 977-984.

- Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry. (2014). Dealing with ticks on school properties? Retrieved from https://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/integrated_pest_management/school/newsletters/documents/RSU2tickIPMarticle.pdf

- Steere, A.C., Coburn, J., & Glickstein, L. (2004). The emergence of Lyme disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 113(8), 1093-1101.

- Daniels, T.J., Fish, D., & Schwartz, I. (1993). Reduced abundance of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) and Lyme disease risk by deer exclusion. Journal of Medical Entomology, 30(6), 1043-1049.

- Padgett, K.A., & Bonilla, D.L. (2011). Novel exposure sites for nymphal Ixodes pacificus within picnic areas. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, 2(4), 191-195.