DACF Home → Bureaus & Programs →Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) → PFAS Response

PFAS Response

The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry (DACF) is committed to ensuring a safe food supply in Maine and supporting our vibrant agricultural community. DACF is taking a leading role in responding to the chemicals known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in agriculture.

On this Page:

What is PFAS?

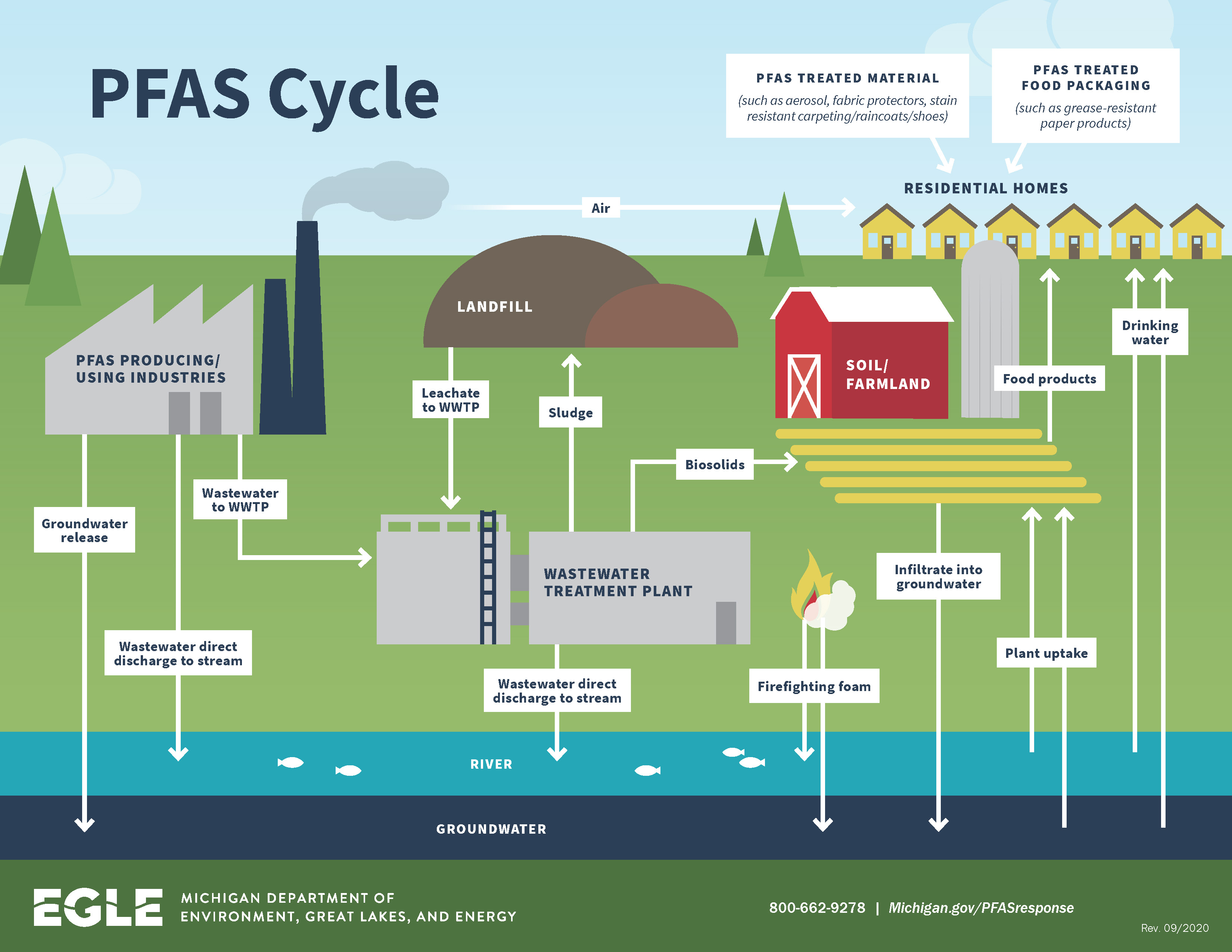

PFAS refer to a group of man-made chemicals known as Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. There are thousands of varieties of these chemicals that repel oil, grease, water, and heat. They became widely used in household products and industrial settings as early as the 1940s and have been used in firefighting foams due to their effectiveness at quickly extinguishing petroleum-based fires.

PFAS have been used to make a host of commercial products including non-stick cookware, stain-resistant carpets and furniture, water-resistant clothing, coated oil resistant paper/cardboard food packaging (like microwave popcorn and pizza boxes), and some personal care products.

What's the risk?

PFAS have a molecular structure with a strong carbon and fluorine bond that is extremely hard to break. This makes them persistent in the environment. This means that PFAS may build up in people, animals, and the environment over time. Studies suggest that these chemicals may affect cholesterol levels, thyroid function, birth weight, liver function, infant development, the immune system, and may increase the risk of some cancers including prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers. Health agencies are working to understand more about the health effects of low level, long-term exposure.

What's the impact to agriculture?

Agriculture and PFAS chemicals can intersect through air, water, and soil. One way that PFAS may enter soil is through the application of residuals such as sludge (also called biosolids) and septage. The application of residuals on agricultural land is a common tool in agriculture as they contain nutrients and other organic matter that can enhance soils and agricultural production. Until 2022, land application of residuals was a permitted and regulated activity by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Land application of residuals is a widespread practice across the US and remains an approved method by the US EPA.

Residuals are created during the wastewater treatment process, and PFAS chemicals can end up in them from everyday household activities as well as from industrial sources. The residuals, when applied to farmland, can contain PFAS substances which can enter soil and water and be taken up by the crops grown on the field, and also into the animals eating those crops. The level of soil or water contamination will depend on the residual source and amount applied, while the amount absorbed by plants and animals will depend on the PFAS compound and species of plant or animal, among other possible factors.

Soil: There is ongoing research on how to remove PFAS from soils, ranging from thermal (heat) treatments, stabilizing with amendments, washing, and other innovations. None are ready for real-world, large-scale use at this time. However, research indicates that some crops may be able to grow safely in PFAS-impacted soils. The level(s) of contamination and detailed sampling and analysis at a farm will help assess whether this may be possible.

Water: PFAS may be removed from water through filtration systems using Granular Activated Charcoal (GAC) or various resins to bind the PFAS as they pass through the substrate. Other technologies are being researched, such as "destruction technology" to break down the fluorine bonds and turn the PFAS into fluorine and carbon.

Plants: Plant uptake of PFAS is a growing body of research. Although there is no current method to remove PFAS from plant tissue once it is present, some PFAS compounds do not appear to readily transfer from soil or water into the edible portions of certain plant tissue. The rate of transfer also varies widely from one species of plant to another. Sometimes this difference allows a farmer to rotate which crop is planted in a particular field in order to maintain operations despite contamination of soil.

Animals: Animals can become contaminated with PFAS by consuming impacted feed or water. They can clear these compounds if the contamination source(s) are eliminated. The amount of time for an animal to depurate (remove the compounds from their body) is variable and dependent upon the half-life of the PFAS compound and the initial level within their body. The half-life is the amount of time it takes for the quantity of the PFAS compound to reduce to half its initial value. This timeline is different for each compound and for each impacted animal species. PFAS in humans have half-lives of years, while certain PFAS in chickens may have a half-life of hours or days. PFOS, a particular PFAS compound, has a half-life of 2-3 months in cattle.

Is food safe?

The US Food and Drug Administration conducts national food sampling studies for PFAS contaminants through its Total Diet Study (TDS). FDA has stated that "no PFAS have been detected in over 97% (701 out of 718) of the fresh and processed foods tested from the TDS." More from FDA about PFAS in food.

What is the Maine DACF doing?

Maine DACF has been at the forefront of responding to PFAS contamination on farms. Maine is not the only state to have permitted land application of residual sludges in the US; however, at present, we are the only state with robust, systematic, and comprehensive efforts to actively test for PFAS and assist those with contamination. Our goal is to help farms navigate the challenges of PFAS. Through our efforts to date, most farms are able to make adjustments and continue to safely produce products.

DACF first began investing PFAS contamination at farms in 2016 when milk at a dairy in Arundel, Maine was found to contain high levels of PFOS. At DACF's request, the Maine CDC created an Action Level for PFOS in milk: 210 parts per trillion (ppt). DACF also conducted three statewide retail milk sampling surveys. In 2020, one retail sample indicated PFOS levels of concern, and DACF worked with the processor to trace the source milk to a contaminated farm in Fairfield, Maine. In 2020, DEP water testing resulting from that discovery detected a second PFOS impacted dairy farm, also in Fairfield. Learn more about DEP's Fairfield investigation.

The discovery of contamination in Fairfield led to a state law passing requiring DEP to investigate soil and groundwater for the presence of PFAS from the land application of sludge and/or septage. DEP must complete its testing of all sites identified through permitting records by 2025. The agency has prioritized these sites into four Tiers (I, II, III, IV) to designate the approximate schedule for sampling. Tier I and Tier II testing is mostly complete and Tier III testing is underway. DACF is working closely with DEP throughout its investigation to assist any sites that may be active agricultural operations. Learn more about DEP's land application investigation.

Maine has over 7,000 farms, the vast majority of which are likely not impacted by PFAS. By undertaking this data-driven investigative approach, Maine will ultimately gain a unique understanding of where PFAS risk may occur on farms, leading to greater confidence in our local food supply.

To date, no federal standards have been created for PFAS in food. This has led Maine to derive a current PFOS Action Level for beef at 3.4 parts per billion (ppb) in addition to its milk PFOS Action Level of 210 parts per trillion (ppt). To learn more about food testing at the federal level, visit the U.S. Food & Drug Administration's PFAS webpage.

Timeline of DACF PFAS Response (PDF)

A list of Maine's existing screening levels for PFAS is available (PDF).

What Happens if PFAS is Detected at a Farm?

DACF's goal is to identify, then limit, or eliminate the PFAS in impacted products. Where PFAS contamination is confirmed in the soil and/or groundwater at a farm above screening levels, DACF is prepared to provide comprehensive assistance. DACF staff first visits the farm to talk to the producers and understand their operation, history, and potential source(s) of PFAS. DACF will craft a sampling plan for that farm, which may include testing of farm products, additional farm fields' soils, water sources, livestock, and feed to determine and monitor levels of contamination. Some sampling can be ongoing to track results over time. DACF staff will conduct the sampling at no cost to the producer.

Based on the sampling results, DACF staff then craft potential mitigation strategies for the farm to incorporate. These are uniquely developed with the goal of adjusting the farm’s management practices to the extent possible while still producing a safe end-product and are based on the specific contamination levels at that property. Examples include installing water filtration systems or blocking access to contaminated water sources, adjusting the use patterns of pastures, growing plants with lower PFAS uptake rates, or utilizing greenhouses to extend growing seasons on clean land. As outlined below, DACF has financial assistance programs to help farms continue to operate while these time and resource-intensive changes are underway.

Product Specific Guidance

Given DACF’s experience on the ground to date with PFAS impacted producers, we have crafted guidance documents relating to dairy farm management and hay production.

If you are a producer and have questions regarding your farm and PFAS, please email pfas.dacf@maine.gov.

Self-testing

Producers concerned about potential PFAS contamination in their fields or water can self-test. However, because PFAS are found in clothing and other common products, sampling must be conducted very carefully and according to certain protocols. The DEP has helpful sampling instructions for groundwater (PDF).

Soil sampling is also a specialized effort. The DEP has guidance for homeowners interested in testing soil. However, for commercial farms, it is recommended that they first discuss their situation with DACF, and if necessary that they work with a third party skilled in soil sampling and familiar with PFAS protocols

Testing can be expensive – not only for the appropriate bottles and gear necessary to take the sample but also for shipping and for laboratory analysis. In total, individual tests may be $200-$500. The full list of PFAS-accredited laboratories is available, however only certain laboratories will accept samples submitted by private citizens (PDF) at this time.

More information can be found at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Guide to Investigating PFAS Risk on Your Farm webpage. This is a comprehensive collection of resources about PFAS contamination in Maine. Topics include steps to determining risks and mitigation options for farms.

Financial support may be available. See the Farm Testing Reimbursement Payment Program section below for more information.

An evolving situation

More research is needed to understand how PFAS accumulates in certain plants cultivated in PFAS-contaminated soils or water and to determine safe levels for consumption. PFAS chemicals can accumulate in the body, and people can be exposed from a variety of sources given how ubiquitous PFAS are in society. People should try and minimize known PFAS exposures whenever possible.

DACF, DEP, and Maine CDC are all working hard to advocate for additional federal support to propel the understanding and science around PFAS forward and establish additional supports for impacted homeowners, municipalities, and farmers. We are also collaborating with other states to continue to learn more about ongoing PFAS research and studies.

Information Disclaimer: The information provided on this web site is only intended to be general summary information for the public. While the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry strives to make the information on this website as timely and accurate as possible, the department makes no claims, promises, or guarantees about the accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of the contents of this site, and expressly disclaims liability for errors and omissions in the contents of this site.