Reducing Carbon Emissions by Mapping Food Data: Courtney Baker

Data shows that about 40% of food produced goes uneaten, making it the single largest category of Maine’s waste stream.

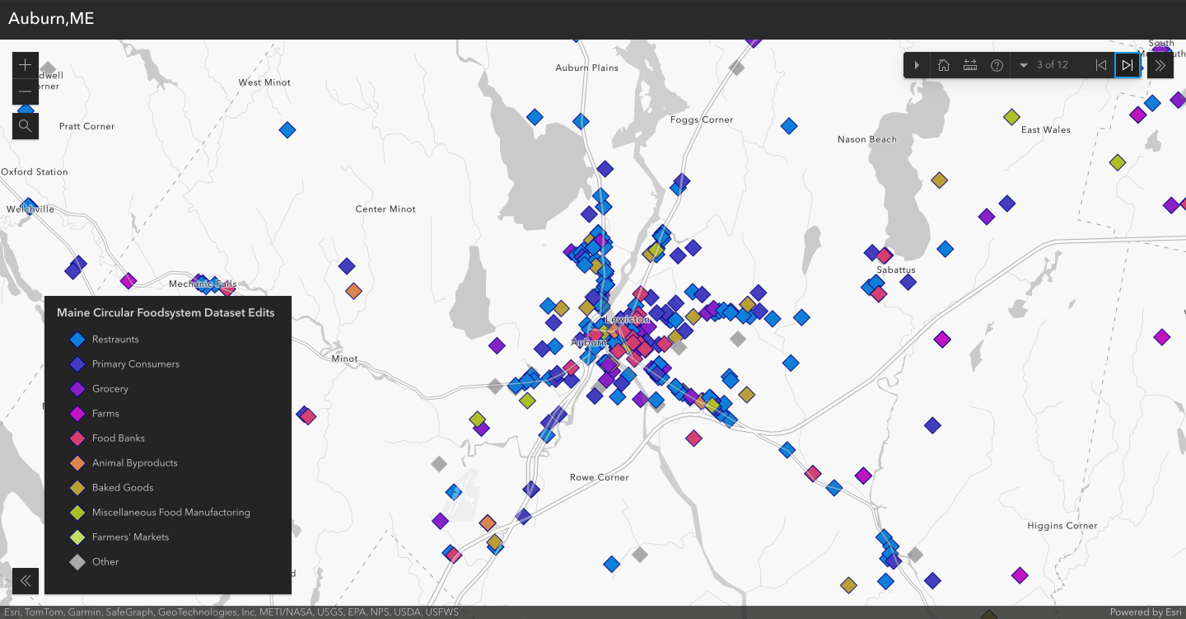

That’s why Courtney Baker, currently a master's student in spatial informatics at the University of Maine, was inspired to create a user-friendly map of Maine’s circulatory food system that can help understand and leverage patterns in conjunction with the Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions. This mapping has the power to reduce carbon emissions and put food back into the community where it can still benefit those in need-- instead of sending it to a landfill.

“We should feed people first, animals second, and then soil—in that order, whenever possible,” she said.

Initiated as a collaborative class project in partnership with the Mitchell Center for Sustainability to use GIS data with real-world applications, she and her colleagues collected data points to explore ways to compile a centralized place that maps food loss.

Now that the class project has ended, Baker continues her work and is earning course credits.

“The best part was talking with community members, not just other students,” said Baker. “I got to talk with people doing work with pantries in Maine, and it made me realize how little I know and how much more I have to learn. The only way to come up with solutions is by harvesting a community’s understanding of it.”

What makes it unique is that she has compiled around 7,000 data points in Maine from available sources that include the US Census, the EPA, Maine GeoLibrary, MOGFA, Maine Federation of Farmer’s Markets, the Maine Food Atlas, Good Shepherd Food Bank, and Feeding America. This data even accounts for the summer fluctuation of food waste using county-by-county data from the Maine Tourism Department.“From there we were able to approximate how much the population increase per zip code during the summer months affected food waste,” she said.

“I want to make this tool useful for people, so they can use it to make important decisions,” said Baker. “It shows food banks, restaurants, farmer’s markets, growers—it’s a compilation of resources to get an idea what’s in the community so they can make the best decisions they can to help solve food insecurity.”

The data points are sorted into one of the following categories: animal byproducts processors, farms, grocery stores, restaurants, farmer’s markets, institutional consumers such as schools, recyclers, and gleaners. These data points are all places that have or potentially have a lot of food waste generation and are a great start to building an infrastructure for Maine’s food system. This infrastructure could be used to answer questions such as where food banks start looking for donors.

But she still has some information she’d like to gather that would make the map even more impactful, including data points on Maine food storage and transportation data, food processors, and smaller food banks like churches and soup kitchens.

“I couldn’t have gotten this far without the willingness of stakeholders to be a part of the data set,” she said. “There are still gaps and holes, but if someone wants to be included, they can reach out.”

As a student of UMaine’s online Spatial Informatics program and currently living in Lubbock, Texas, Baker says her work on Maine’s food data mapping has also informed her about her local systems as well.

“That’s a reason I love this,” she said. “You can do this data work from anywhere in the world and have a positive local impact from afar.”