February 23, 2021 at 1:24 pm

It’s a cold, calm February morning when I meet Maine Game Warden Jeff Beach at the Norridgewock airport to go over our flight plan for the day. Jeff is one of three game warden pilots for the state. He arrived at the small airport earlier to fuel his Cessna for a day of survey flights. As a game warden pilot, Jeff patrols the state of Maine from the sky, but he also works on a variety of fish and wildlife projects, including stocking fish in remote ponds, eagle nest surveys, and tracking collared bears, deer, lynx and moose. Our flight today will focus on deer surveys.

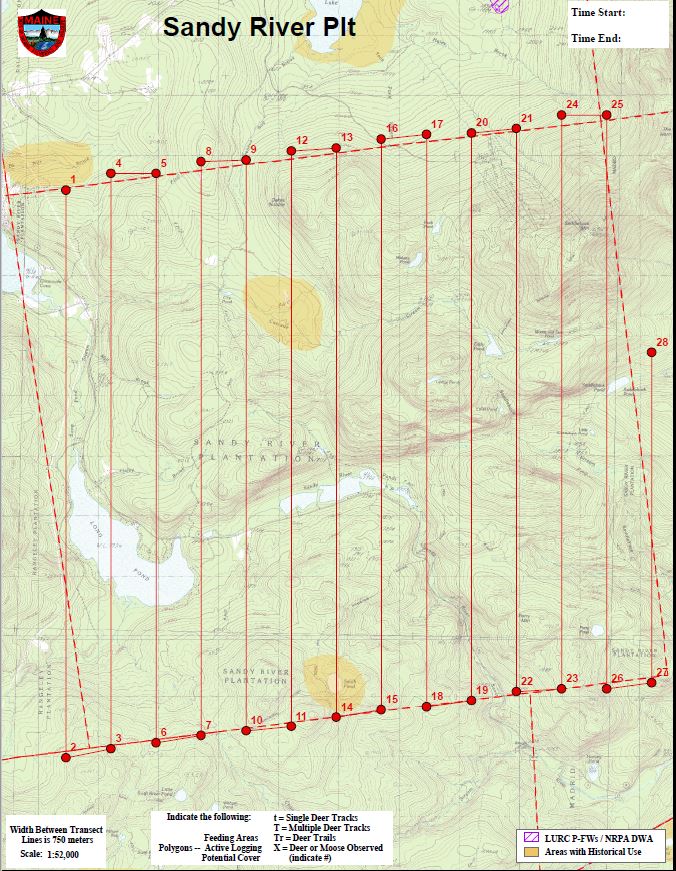

The goal of deer survey flights is to record deer tracks and trails in existing deer yards and document new areas of potentially important winter habitat for deer. We jump in the plane, buckle up and check our headsets to make sure the mics are working. I fire up the mapping system on the iPad that will follow our survey progress, while Jeff radios the tower that we are preparing for takeoff. He motors us down to the far end of the runway where he runs through his systems, asks if I’m all set, and we’re off, lifting above the farm fields below. It’s a clear day and we can make out Katadin to the north and Mt. Washington to the west.

The winds are calm today, but my pre-flight routine always includes one chewable Dramamine tablet to prevent motion sickness. These types of low elevation surveys are not for everyone. Small aircraft flying through the mountains of Maine can sometimes be a rough ride and being able to “fly well” is considered an asset for this type of work.

Today, we plan to visit four towns in the Rangeley Lakes Region. It takes about an hour to fly the entire township, depending on the size. We time our surveys for when the sun is directly above, limiting shadows on the ground that can make it hard to see deer tracks and trails. Our flight plan usually includes alternate survey towns because conditions can change as the morning wears on. The western mountains are notorious for rough afternoon winds, so it’s good to have other areas we could shift to, if the winds pick up in the mountains.

We arrive in our first survey township and line up on the transect line. Jeff flies us low along the line, back and forth covering the entire township. The lines are laid out to ensure we survey the entire area for deer tracks. I stare out the window, looking at the ground and tracking our location on a paper map, making a pencil mark for every deer trail and track we cross as we fly back and forth covering the entire township. I also record things like active forestry operations, moose, otter slides, or kill sights where predators and scavengers create large blood-stained areas in the snow around a carcass. Some townships in western Maine have little to no deer sign in the winter, primarily because of habitat and steep topography, so recording additional wildlife observations helps my mind stay engaged during the hours of staring at the ground. Where deer are prevalent on the landscape, I mark individual tracks and well-worn trails, creating a snapshot of winter deer use throughout the township.

I checked my weather monitoring station in Coplin Plantation the previous day and snow depths were over three feet deep. Once snow depths average a foot or more, conditions start to become difficult for deer, triggering migration to dense conifer forests referred to as deer yards where they form a network of trails through the snow-covered forest. Deer yards are dense stands of mature conifer trees, where evergreen boughs intercept heavy snows, and provide shelter from cold winter winds. When tree species like spruce and fir catch snow on their branches before it hits the ground, the snow goes through a process called sublimation, where it turns from a solid ice crystal to a vapor, evaporating before it falls to the ground. As a result, the snowpack in the dense conifer cover of deer yards is noticeably thinner than snow cover in more open habitat. Deer have learned to gravitate to these dense conifer areas because of the thinner snowpack and shelter from harsh weather conditions. The milder conditions found in deer yards also reduces the amount of energy deer use, which is critical for survival during the winter when food resources are scarce. Although deer are adapted to survive winter on the limited diet found in the shelter of deer yards, they can deplete their energy reserves and starve if they are forced to spend a long winter wallowing in deep snow and exposed to harsh weather in open habitat. The next time you are out on a cold windy day, find an area of dense conifer cover and go into the stand. Like deer, you will notice a comfortable difference in the conditions under the dense conifer and will be reluctant to venture back out into the deep snow of the open fields, or under the open canopy of leafless deciduous trees, where the wind blows through you.

Northern wildlife species including snowshoe hare and lynx have physical adaptions, like big feet, that help them to stay on top of the snow. Deer take a different approach to snow travel and rely on the behavioral adaption of establishing a network of trails in deer yards for survival in the deep snows of Maine’s long winters. The snow along deer trails is packed well enough to walk without snowshoes, but one step off the beaten path results in sinking up to your waste in deep powdery snow. At my weather station in the Coplin Plantation deer yard, I occasionally see tracks where deer step off the packed trail and wallow forward through the snow, sinking nearly 20 inches with every step. Without an established trail system in the protective cover of deer yards, deer become exhausted, pushing through deep snow to find browse, or escape predators.

Biologists have been surveying and mapping deer wintering areas throughout Maine for several decades and the results from our surveys create and maintain maps of deer wintering areas. Knowing where deer spend their winter helps us protect winter habitat from impacts like development or working with forestry operations to ensure enough habitat remains to provide winter cover. Some deer wintering areas are protected through regulation, although much of the mapped habitat relies on private landowners voluntarily managing their property with wildlife in mind.

For more information about white-tailed deer visit mefishwildlife.com/deer