March 14, 2025 at 2:48 pm

Subnivean Secrets

Scientific knowledge grows from the roots of unanswered questions. Through curiosity and exploration, we dig up answers which become seeds of further questions. Biologists cultivate our understanding of the natural world by making observations beyond our field of view to investigate intricate connections within our ecosystem, study secretive species, and examine hidden habitats in all seasons, even winter. MDIFW biologists take to the ice, snow, skies, and even underground to collect data, conducting creel surveys, visiting bear dens and bat hibernacula, monitoring camera traps, completing aerial moose surveys, and more! At first glance, winter may seem like an uneventful time for wildlife, but there is a lot more going on than meets the eye.

-Henry David Thoreau

Ice anglers are also accustomed to the idea of life veiled by layers of winter. Others may consider cold temperatures and the ice that forms across our lakes and ponds as temporary barriers to waters enjoyed throughout the summer months, but to them, hard water spells opportunity for access to some of our state’s greatest treasures. When a flag flies and a brook trout is hauled up through the ice, winter no longer feels stark and quiet.

On land, it’s easier to forget there is a living world beneath our feet. Maine’s winter landscape, stripped of the songs of spring, smell of summer blooms, and colors of fall, leaves the impression that when snow falls, we are left only a blank canvas on which a new year will be painted. But the white of winter does not erase life; it conceals and even protects it. The approach of spring brings a unique opportunity for any backyard naturalist to explore just how much wildlife activity has gone unnoticed throughout the winter. As the last of the snow melts away, watch as secret tunnels become exposed. It's a library of winter survival stories and a map of a special place called the subnivean zone.

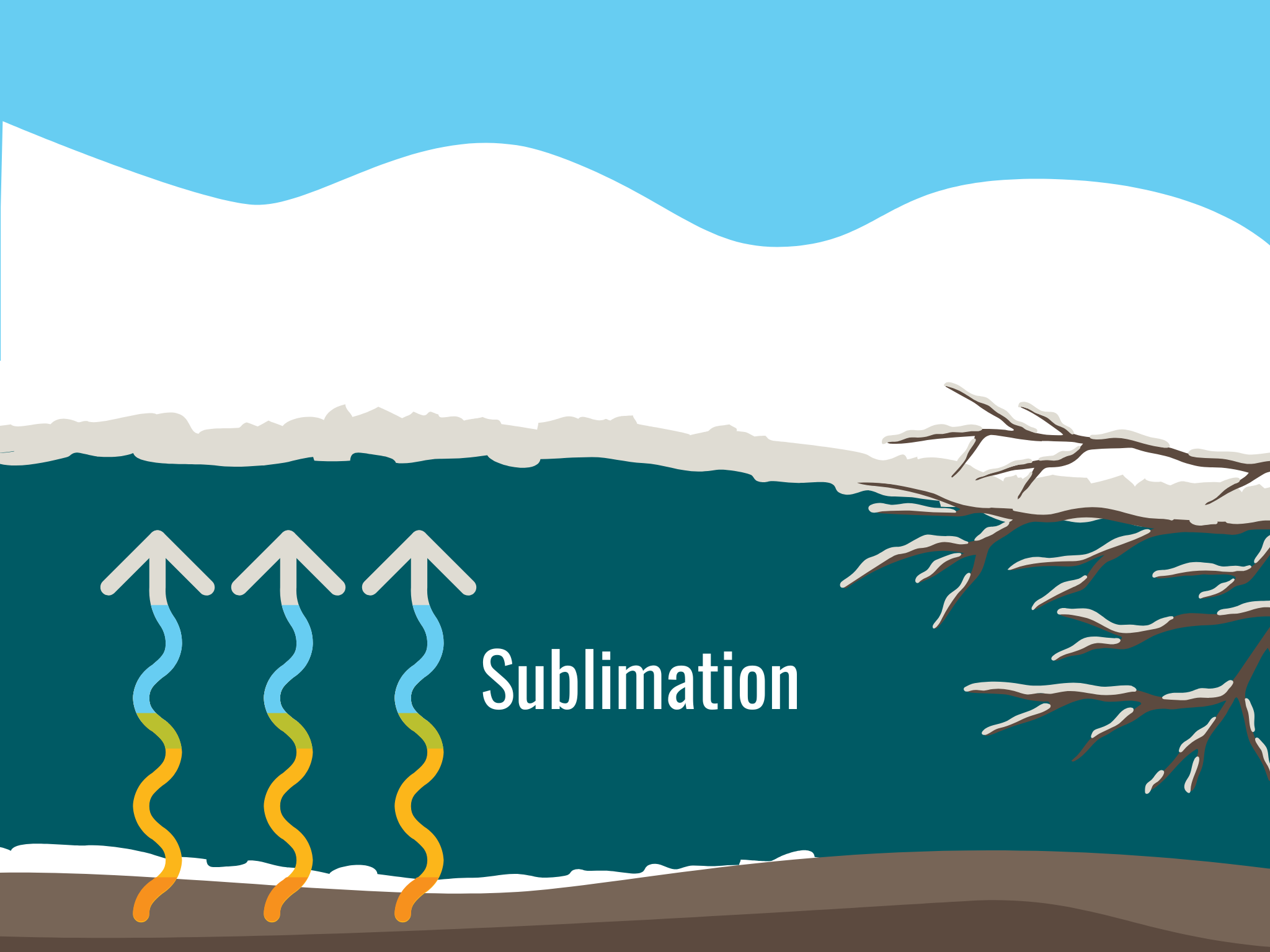

Subnivean Sublimation

The term subnivean is derived from the Latin “sub” meaning under, and “niv” meaning snow. The subnivean zone is the ephemeral place between the surface of the earth and the base of the snowpack, a layer of space in which wildlife use winter to their advantage for survival.

This unique habitat forms for two reasons. The first is that snow is held up off the ground by branches, grasses, and other vegetation, creating pockets of air. The second is that heat from the ground forces snow from a solid state to a gas without passing through a liquid stage, a process called sublimation. As this vapor rises, it cools, condenses, and refreezes, forming a dense icy layer that becomes the foundation of the snowpack, and the ceiling of the subnivean zone. Snow may be cold, but it’s also a great insulator. Ruffed grouse use this to their advantage, roosting in caves within the snowpack. As more snow piles on, it shields the subnivean zone from the cold, creating a temperature-stable sanctuary for an assortment of microorganisms, fungi, plants, and wildlife.

Subnivean Species

Maine’s wildlife uses three basic strategies to survive winter. Some species use their impressive endurance and unmatched navigation skills for migration to wintering areas with better food supplies and warmer temperatures. Others feast through the fall then stick around and tough out the snowy season by taking shelter underground and slowing their bodies into dormancy until spring. The third approach is to stay home, stay active, and persevere during months of cold temperatures, short days, and limited food. This is the strategy used by three of subnivean zone’s most prolific inhabitants- mice, voles, and shrews.

The subnivean zone provides these species with more than just a temperature-stable environment. It also facilitates access to food. Seeds, nuts, grasses, lichens, fungi, and insects are all available in the subnivean zone, helping mice, voles, and shrews keep up with the high energy demands of winter, fueling their extraordinarily high metabolisms. In an endless quest to feed, they race through labyrinths of foraging runways that also serve as escape routes and extensive highways to various chambers for nests, latrines, and food caches. In the winter, the only subtle clue on the surface that these tunnels exist are tiny tracks leading in and out of one-inch holes into the snow. But as the snow melts, a cross-section of the subnivean system becomes visible. With bedrooms, bathrooms, pantries, and even a breakfast nook, these species have all the comforts of home in the subnivean zone, allowing them to extend their breeding season, and stay out of sight from predators.

Unlike snowshoe hares and ermine, mice, voles, and shrews don’t develop white coats in winter. Their dark fur stands out against blankets of snow, putting them in danger of detection by predators of all shapes and sizes. Sheltered by their snowy roof, their chances are much higher, but some skillful predators have developed strategies to capitalize on winter’s buried buffet.

Short-tailed weasels, also known as ermine, are agile carnivores that hunt the subnivean zone from within. Their slender frame is just small enough to infiltrate tunnels at high speed and catch their prey off-guard. Red foxes are famous for their acrobatic mousing style in winter. They patiently pinpoint small mammals below the snow using their acute hearing, then leap upwards and pounce straight down, punching through the snow to reach their meal, collapsing tunnels in the process.

Aerial predators are also keenly aware of hidden hunting opportunities in the subnivean zone. The sounds of scurrying rodents are muffled by the snow, but not enough to go unnoticed by owls. Owls have feathers that form a facial disc to direct sound to large asymmetrical ears, allowing them to zero in on prey with precision. Their feathers are specially adapted for silent flight, a unique ability for hunting on quiet winter nights. Some scientists believe the primary benefit of noiseless wings is for stealth, limiting the chance their prey will notice them and escape. Others believe owls adapted a silent approach to prevent flight noise from impeding their ability to locate their target.

Subnivean Shifts

Like vernal pools, the subnivean zone is a seasonal habitat. As spring arrives, subnivean zone wildlife will shift their strategies along with the season, but the remnants of tunnels are not all that’s left behind. Throughout the winter, the activity of subnivean wildlife, fungi, and microorganisms has been contributing to nutrient cycling and soil health. The lush green of springtime depends on ecosystem services like these being provided behind the scenes.

As scientists continue to learn about the subnivean zone, it becomes clear that its impact extends beyond winter, but with every answer comes more questions. How does subnivean zone wildlife respond to winters with little snow? What happens if winter arrives late, or spring weather starts early? Some aspects of the subnivean zone remain a mystery for now. As spring begins, birds return, bears emerge, and peeper call, we wonder about other intricate connections between secretive species and hidden habitats that we haven’t yet discovered. As you head outside this season, we encourage you to look beyond your field of view, listen, learn, and never stop asking questions.