May 5, 2022 at 11:22 am

Maine Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project 2022

Gaining a clear understanding of the abundance and distribution of species over time is instrumental in making informed wildlife management decisions to protect our state’s biological diversity. With over 33,000 square miles of Maine to survey, and 34 species of reptiles and amphibians, accurate species mapping is a challenge! To help cover this vast area, Maine’s wildlife biologists rely on community members to share their observations, including you!

By collaborating with professional biologists, citizen scientists can make important contributions to our understanding of Maine’s natural history. The Maine Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project (MARAP) is one of the longest running citizen science projects in New England. Since the project was launched in 1984, hundreds of volunteers have submitted thousands of observations of Maine’s 34 species of reptiles and amphibians. With each submission we gain a more complete biogeographic picture of the state’s herpetofauna. The fact that 1/3 of Maine’s reptiles and amphibians currently listed as State Endangered, Threatened, or Special Concern makes closing this knowledge gap even more pressing.

How you can help

Whether or not you have participated in MARAP before, the 2022 is a very exciting time to get involved! Data submitted this year and next will be the last to be included in the third edition of Maine Amphibians and Reptiles, scheduled for publication by University of Maine Press in 2024.

You don’t have to be an expert at identifying reptiles and amphibians before you begin. Getting out there to survey will help you improve those skills along the way. If you’d rather get a head start, visit our website to become familiar with each species. Learning about their habitat, seasonal activity, and behavior can give you clues on where, when, and how to find each species. It’s also okay to simply report incidental sightings during any outdoor adventure whether in your own back yard or the North Maine Woods.

Participation is open to citizen scientists of all ages and experience levels, there is no minimum number of observations required, and our new online submission form makes contributing to the project faster and easier than ever!

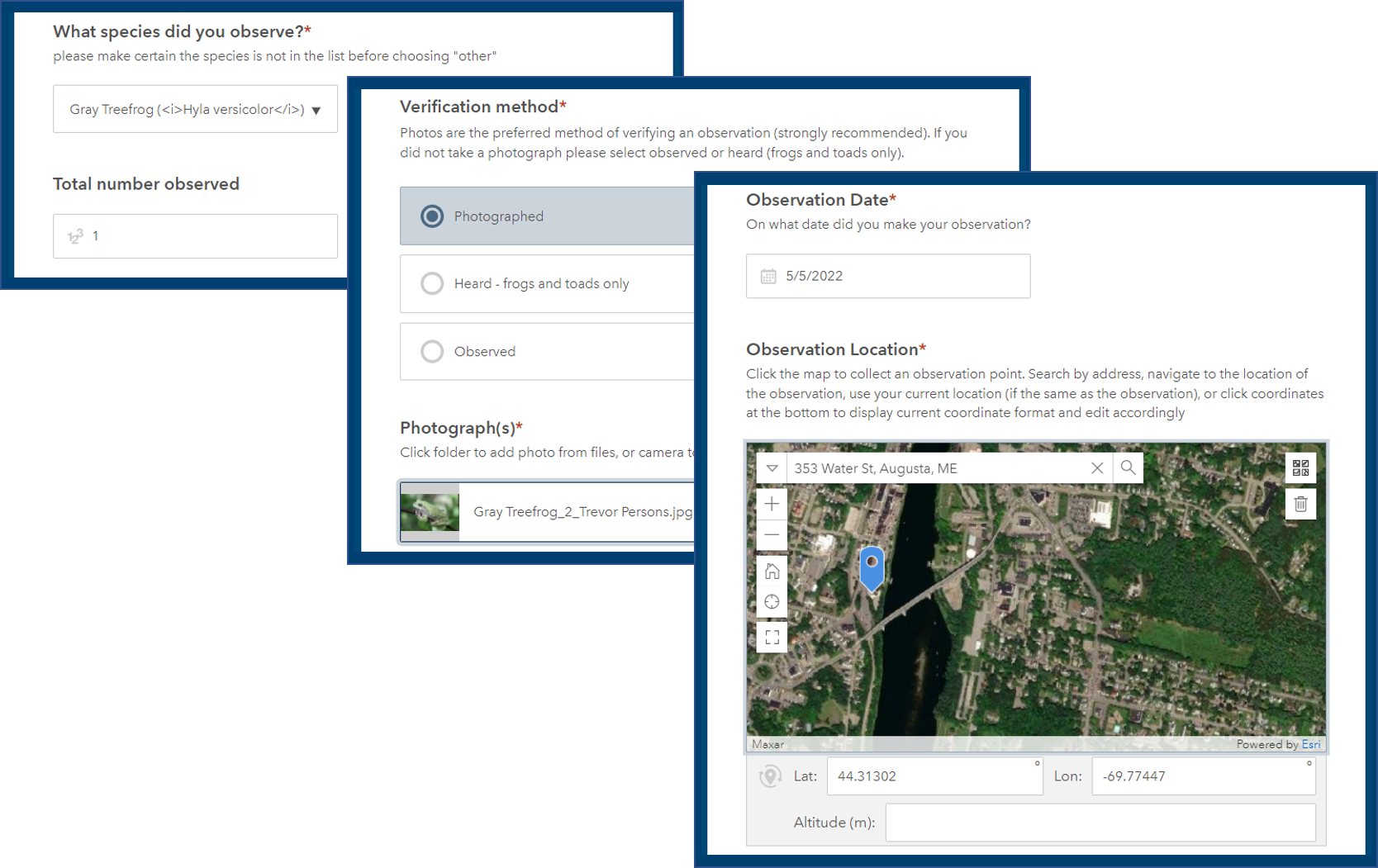

Any time you spot a salamander, frog, turtle, or snake in Maine, take a photo and submit it with the following information:

- Number of individuals

- Species (don’t worry if you are unsure, MDIFW biologists will review every record)

- Date

- Your contact info

- Location- A street address is fine, or use the map feature right in the submission form to add a GPS location.

That’s all there is to it! Adding additional notes including a habitat description is helpful but not required. You can upload your data using the online form when you have a connection at your computer, or download the app ahead of time to use it offline in the field.

Uploading your observations through the popular iNaturalist website or app is also a great way to share data with MARAP. This might be a good option for those who are still learning to identify species because the app provides assistance with the identification of your photos.

Where to look

You’ll likely be surprised just how many wildlife species you see when you slow down and take a moment to look! Many of Maine’s reptiles and amphibians live in forested areas near or in ponds, marshes, and swamps. If the area is wet, they may be nearby! Look under rocks or logs for a fun surprise (carefully returning them to their original positions to maintain the habitat), or listen for calling frogs for clues! Spring and summer are excellent times for wildlife scavenger hunts.

One of the priority goals of the 2022 MARAP field season is to fill in geographical gaps in data on species distributions. Even for the most common species such as painted turtles and bull frogs, there are still several areas where observations have not been recorded. Never assume that your sighting isn’t valuable just because it is a common species.

Data gaps could be close to home, but are most common in more remote areas that are difficult to access or visited less frequently such as the North Maine Woods. If you vacation at a camp on a lake or pond in Maine, we need your records! The farther north and more remote your explorations, the more valuable your sightings are likely to be. If you enjoy any type of outdoor recreation, the right MARAP experience for you might be an adventure from the following list of geographic priorities. As always, please be prepared, stay safe, and respect private landowner wishes. Keep in mind that some of these locations may not be accessible or safe until later in the season (when snow is gone and roads are less muddy).

- Experienced paddlers might consider a trip on the Allagash and St. John Rivers to help add snapping turtle and wood turtle observations in northwestern Maine. Southeastern Aroostook and northern Hancock/Washington Counties have very few records even for common species, but a hike or paddle in that region could help fill many species gaps.

- Baxter State Park has been surveyed relatively well, but areas farther north in northeastern Piscataquis County still need records. Consider surveying for reptiles and amphibians during a fishing trip to Mooseleuk, Munsungen Lake, or another waterbody in the region.

- A hike at Mount Blue or Tumbledown conservation area could be a fun adventure, especially if you are interested in contributing new reptile records. There is a data gap in the Sandy River region west of Farmington for milksnakes, smooth greensnakes, red-bellied snakes, and snapping turtles.

- If it’s frogs you are interested in, the St. John River along the border in northeastern Aroostook County is an area of special interest for pickerel frogs, which still have not been documented there.

- Extreme western Maine – the northern portions of Oxford, Franklin, and Somerset counties (west and north of Kingfield and Jackman) – is also poorly surveyed. Simply documenting a green frog or a redback salamander in these areas is quite likely to represent a novel township observation.

Share your observation with us