March 17, 2023 at 9:48 am

Being a wildlife biologist is a highly sought-after profession and career, attracting many individuals who have an interest and love for wildlife, enjoy outdoor recreation, and prefer to spend their days among the trees. While the unique experiences occasionally produce envious photos snuggling a bear cub during a den visit, a moose that’s been immobilized to safely relocate it, or a banded peregrine chick that closely resembles a pile of mashed potatoes with a beak, the reality of the job can be much more challenging than the images lead on. The reality is, the days often begin before the early summer sun rises, can last long after the sun is gone, and endures all extreme temperatures, topographical challenges, and the difficulties of long journeys alone with heavy gear.

The breadth and depth of work that’s conducted by wildlife biologists at Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife (MDIFW) is usually unfamiliar to most, and the commitment is frequently unconsidered by many. While the reward for this career is high for those who love it, not all can hack the demands of the job.

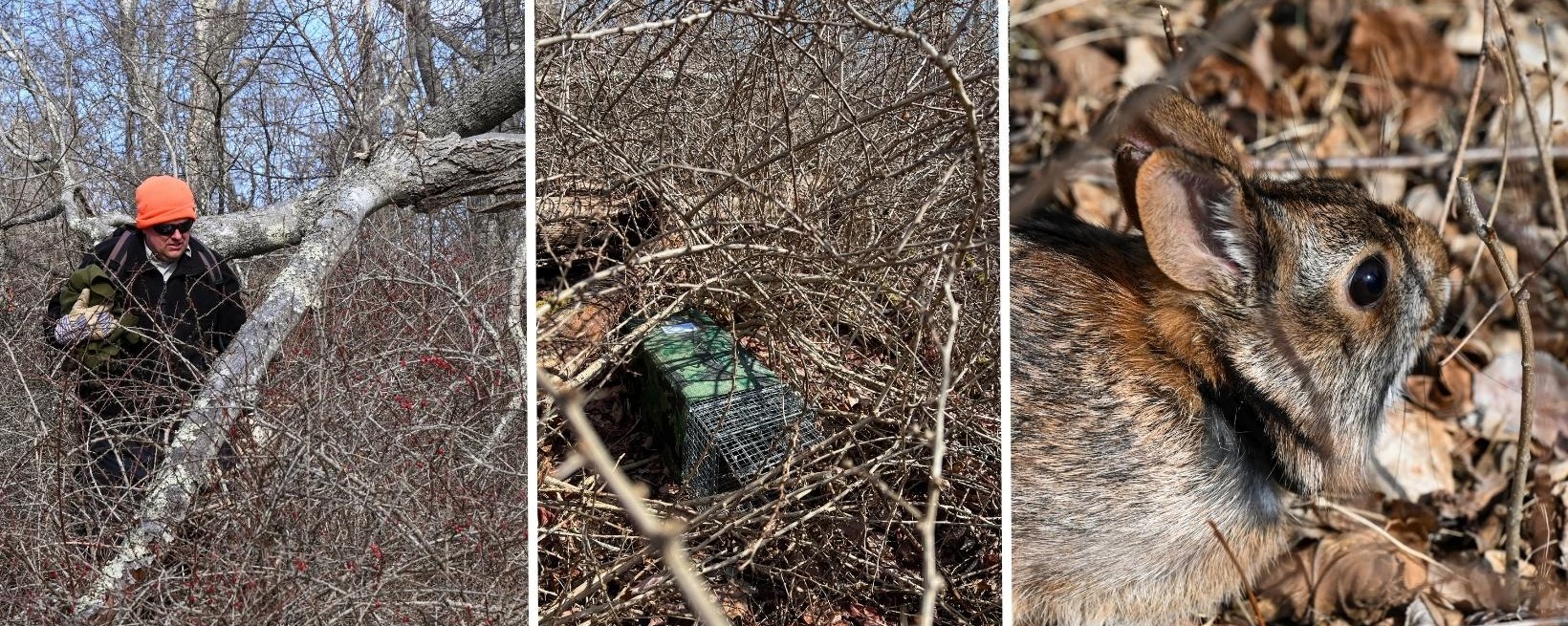

Thorns and Thickets

Capturing and surveying for bunnies, New England cottontail (NEC) specifically, might sound ‘easy’, but it isn’t for the faint of heart. NEC was once a common rabbit in southern and coastal Maine, but are now a state Endangered species, with an estimated 300 individuals in only six towns in the state, all south of Portland. To survey for presence or absence of NEC, biologists search for fecal pellets that are sent out for genetic testing to determine species (you can’t tell the difference between the pellets of NEC, the abundant snowshoe hare, or the invasive eastern cottontail) Seems simple, right? Nope. These little rabbits live in areas of extreme thickets and thorns, making it next to impossible to push and pull your way through vines that hook onto your clothing, scratch your skin, and pierce through your layers, all during cold, windy, winter days. While trapping these rabbits is more fun than collecting fecal pellets, it still requires you trudge through the same complex habitat and endure freezing temperatures. Captured bunnies are sent to a captive breeding program to help build populations across New England or released in different locations to establish new populations.

Stomachs of Steel

Maine’s moose management exposes one to some of the most versatile monitoring efforts for wildlife. The seasonal expectations contrast greatly, beginning with aerial counts from a helicopter. While flying a straight line to count moose isn’t too bad, conducting composition counts (sex and age) throws some curves, literally. Often, the helicopter will have to make sharp circles to determine the sex of an individual moose, making even some of the most iron stomachs feel queasy. Additionally, and unfortunately, much of wildlife biology is having to look at dead organisms to evaluate cause of death. Conducting necropsies on moose calves takes up a significant amount of time for biologists in the North Maine Woods, going to the most remote places in the state to look at often 50+ dead moose over just a couple of months. Not only are these journeys to reach an expired animal long and laborious, but it also highlights the many challenges wildlife face with diseases and parasites on a daily basis. More recently, Maine and other Northeast states have been collaborating to evaluate the efficacy of using game cameras to monitor moose health, look at twining rates, cow to bull and cow to calf ratios, and more. While looking at images on a camera isn’t challenging, placing 80 cameras in the middle of nowhere can be. With the short days, it’s not uncommon to be trudging through the woods in the dark. Sometimes, a four-wheeler or snowmobile can be used to reach a remote location, and other times, you’re crossing a fast-moving stream or partially frozen beaver dam by foot with some heavy gear.

Mosquitos, Black Flies, and Bears…Oh My!

In spring months, MDIFW bear crew members seek to trap and collar female bears, providing tracking opportunity to her winter den where biologists evaluate the health of the female and any cubs she may have had. This spring endeavor requires weeks at a time in the heat and humidity, battling swaths of mosquitos and black flies, setting and checking traps repeatedly, and eventually, catching a bear. If it’s a female, she’ll acquire a collar for tracking, a small tattoo for identification, and will then be released. Understanding how to set a trap for a bear, or any species, requires more attention to detail than one might think. Biologists are looking to specifically capture a front leg. Securing a front leg ensures the animal can’t gain enough traction to injure itself. Bait is set carefully, a particular distance from the trap, and in a very specific placement to lead the bear to place its front foot on one small opening of a cable in the middle thousands of acres of woods. The bear receives a health work-up and might acquire some equipment before being released unharmed. During the winter months when bears are in a state of torpor to endure a long period of time with little to no food, the tracking to dens begins. A den can be a small cavity in a tree, a dig under a pile of brush, or some other unsuspecting spot in the woods. Biologists have to sneak up to the bear carefully and quietly, immobilize her, and wait for her to…remain unconscious. Then, it’s safe to go in to retrieve the sow and her cubs to measure, weigh, tag, and note their health, before returning them safely to their den.

Birds, Boats, and Blocks

Into birds?? Then you might have heard of MDIFW’s Bird Atlas Project – five years of consistent effort collecting data to map the distribution and often abundance of Maine’s breeding and wintering bird species.. The international standard is for these kinds of regional (i.e., statewide) surveys to be repeated at 20-year intervals to monitor population trends of birds. Maine conducted its first breeding bird atlas between 1978 and 1983, prompting an overdue need for another atlas project in 2018. Since birds are everywhere on the landscape, biologists, volunteers, and citizen scientists had to be, too! From the far northern reach of the state where deep, off-trail snowmobiling is required, to offshore boating along the islands in the Atlantic Ocean, birders and professional biologists have been contributing thousands of hours to this endeavor by land, air, and sea. This project officially came to a close on March 15th, 2023 after over 6,500,000 volunteers helped accomplish this incredible undertaking to monitor and completely survey over a third of the state! What’s more impressive is the collaborative effort and partnerships between MDIFW staff and other organizations such as Maine Natural History Observatory, Maine Audubon, Biodiversity Research Institute, and Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Thank you to everyone who was involved for making this happen!

Rockets and Jewelry

The reintroduction of the wild turkey in Maine was a labor of love, taking years of attempts that finally took in the 1970’s after almost 100 years of being extirpated from the state. While not all are fond of our wild turkey population, their value to the ecosystem as both a predator and prey enhances the habitats and wildlife around them. To keep the population healthy across the state, occasional surveying is required. Recent statutory changes has initiated electronic registration and tagging of turkey in the spring, prompting an action plan to monitor turkey harvest through a banding study. Turkeys are known for milling around in constant search of food. Their keen eyes keep them relatively wary of their surroundings, so capturing a rafter of turkeys can be challenging. For days to weeks, baiting is required to get the turkeys habituated to a location and ideally even a consistent return time to the bait every day. If returning is consistent, biologists will arrive and bait before the sun rises to set up a rocket-net. A box holding a large net with weights attached is wired to explosives and rockets that when triggered, shoot the net out and over the turkeys, hopefully before these large but fast birds can escape. The strength and size of these birds can be challenging to control. With strong legs, sharp spurs, and powerful wings, it’s important to protect your eyes and face during the process. Each bird receives a head cover to help calm the animal, then with shivering hands from the often-freezing temperatures, each bird is equipped with a jewelry (a marked band) that will be turned in if harvested. The patience and consistency required to capture and band an adequate number of turkeys is arduous and requires significant time, but worth ensuring this species remains healthy and abundant.

An Aerial View

Some things in wildlife research is best evaluated by air. MDIFW is lucky to have several wardens with pilots’ licenses and willing to take a wildlife biologist into a small, fixed-wing aircraft to conduct Deer Wintering Area surveys. With tight quarters and hopefully excellent eyesight, you quickly identify various fixtures on the landscape to best orient yourself while flying. Taking your finger and tracking along pre-developed flight lines, you attempt to keep with the speed of the aircraft while looking down 500 feet to the ground, seeking tracks and trails from deer and marking it on your map. Easier said than done. Looking up and down for an hour or more may start to impact your vertigo, and if that doesn’t get to you, the banks you take at the end of each survey line might. But seeing the vast forested land that hosts Maine’s diverse wildlife is unforgettable and is worth the trip! In the summer months, biologists will begin conducting heron surveys, looking at population trends over time. Circling a heron nest is a little more dicey than straight lines, but worth the effort!

Cryptic Critters

Maine has some cryptic wildlife with secretive lives, sometimes making it difficult to identify adequate habitat. It can take out-of-the-box thinking to browse a map in search of cold, high elevation streams to find a spring or dusky salamander. After 36 years, MARAP, or Maine’s Amphibian and Reptile Atlas Project, is one of the longest running citizen science projects in New England. Effort has been spent filling in data gaps of the 36 species of herpetofauna across the state to determine presence and absence, abundance, and population trends. While interactions with reptiles and amphibians are always enjoyable for MDIFW staff, not all are suited for a go-around with some of Maine’s swift and elusive species. The black racer for instance, requires a level of great athleticism to launch and catch before the reptile slips through your hands, or the careful handling of the well-known snapping turtle which boasts a large head, mean bite, and long, sharp claws. A truly unique experience is to participate in “Big Night”, where the warm rainy spring nights bring out thousands of amphibians simultaneously as they move from upland areas to their breeding grounds. While this sight can be spectacular, you have to be a night owl! Be prepared to stay up all night to get an effective count for the migration monitoring!

Acoustics and Caves

In the hottest months of the summer, bat detectors are deployed across the state to evaluate bat occupancy and population trends. The method of detecting bats is relatively simple – an acoustic detector is deployed on the landscape, typically on a long pole in an open area where the microphone can record calls that can then be put onto the computer for identifying specific species. It’s the action of deploying the detectors that is the challenge. Many areas of Maine are remote with rough terrain. Whether it’s on a steep mountain, a talus slope (rocks that have fallen from a cliff and created crevices), in the middle of a marsh, or simply at the end of a field, the trek can be labor intensive, all while carrying gear. Navigating hummocks (mounds of grasses) in marshlands might have you stumbling across the landscape, while dense shrubs and alders can make movement restrictive, or long, un-mowed fields can create excellent tick habitat as you trudge through. Once retrieved, recordings (as much as 60 gigabytes per site and totaling several terabytes statewide) need to be cataloged and analyzed to determine which species were present at each site. In the winter months, some bat species hibernate in caves, creating areas of tight spaces to navigate to find the colony. At every turn, Maine does a great job of getting you muddy, wet, pricked, sweaty, cold, and exhausted on any given trek in an effort to monitor a wildlife species.

Career Quests & Job Journeys

Much of this job is getting comfortable being uncomfortable. It’s a lifetime of learning, honing in skills, challenging yourself with unique situations, and above all, being confident in your abilities. Being a wildlife biologist is competitive, a labor of love, and requires a curious mind and can-do attitude. The reward for working with wildlife is great, but well-earned and deserved! If you enjoy Maine’s wildlife in any capacity, thank a wildlife biologist for their constant work and commitment to the job in any and all conditions! And if you’re someone who is an aspiring biologist, here’s a few tips: get a four-year degree in an applicable science field. This is the building blocks of knowledge for this line of work and can help you better understand the dynamics of wildlife management and conservation. Often times, our biologists have advanced (i.e, master’s or doctoral degrees), so keep your options open while in school. While in in your undergraduate program, discuss possible work or volunteering opportunities with your professors, and reach out to a wildlife biologist and ask if you can volunteer or join them in the field. Going along with a biologist in the field can help you acquire greater understanding of the field work, whether or not you’d enjoy the work, and helps you build relationships and skills early on. It can also help you understand some of the logistics that have to be worked out, such as landowner permissions, specialized chemical immobilization training, data compilation, and data analysis. Lastly, get exposure and build a resume and submit your information for Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife for potential contract opportunities at mefishwildlife.com/careers.