July 29, 2016 at 3:38 pm

Adult great blue heron, known as "Pine Pond," trapped and tagged with a GPS transmitter in Orono. (Photo by Brittany Marinelli)

This spring, MDIFW tagged five adult great blue herons with GPS transmitters as part of an ongoing effort to better understand the state’s great blue heron population. After a significant decline in the number of nesting pairs on Maine’s coastal islands from the 1980s to 2007, MDIFW listed the great blue heron as a Species of Special Concern and began a citizen science adopt-a-colony program called the Heron Observation Network. By marking and following individual adults over several years, MDIFW hopes to learn new information regarding daily movements, habitat use, colony fidelity, migration routes, and wintering locations of Maine’s herons.

Students from Center Drive School in Orrington pour bait fish into bait bin to attract a great blue heron. (Photo by Nancy Swanson)

Students and teachers from several schools across the state played an important role in the field work leading up to the tagging of the five herons. The students and teachers set and checked minnow traps, identified and measured the baitfish caught, and placed the baitfish into a bait bin in order to get a great blue heron to regularly feed from it. They also used game cameras to “watch” the bait bins when they were not there themselves. After a heron was accustomed to feeding from the bait bin, MDIFW and researchers Dr. John Brzorad (Lenoir-Rhyne University) and Dr. Alan Maccarone (Friends University) set out an array of modified foothold traps near the bait bin to capture the heron so they could tag it with a GPS transmitter. The use of modified foothold traps has been perfected by Brzorad, and involves watching the set traps from a blind until a heron steps into one of the traps. Once trapped, it is then quickly retrieved by the researchers for processing. The bird is kept calm with a hood over its eyes while researchers take measurements and a blood sample for sexing, and attach the transmitter.

Great blue heron perched on the edge of the bait bin. (Photo by Bill Freudenberger)

The transmitters were purchased with a grant from the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund, and represent the cutting edge of telemetry technology and transmit GPS locations via the cell phone network to an open source website (www.movebank.org). The units also collect xyz accelerometry data on behavioral postures that quantifies time-energy budgets. Being solar-powered, they are expected to provide years of data for each tagged heron. Fully charged, the units collect 288 GPS points and 360 behavioral (accelerometry) tracings per 24-hr period. The data is available on www.movebank.org for the students, citizens, and conservationists of Maine to use in education and to help make conservation decisions. Brzorad and Maccarone have been using these same transmitters since 2013 and have paired nearly 20 birds (great egrets and great blue herons) with school systems in five other states. In Maine, the students involved in this spring’s field work ranged in level from grades 1-12 and were from the following schools: White Pine Programs in York, Harpswell Community School, Gray-New Gloucester High School, Nokomis High School in Newport, Old Town High School, Haworth Academic Center in Bangor, and Center Drive School in Orrington. Thanks to their efforts, five great blue herons were trapped and tagged in Orrington, New Gloucester, Orono, and Palmyra:

- “Snark” is a male trapped in Orrington and adopted by Haworth Academic Center in Bangor. The students chose his name because they had recently read Lewis Carroll’s poem, “Hunting of the Snark."

Snark spotted at his nest. The transmitter is circled in orange. (Photo by Jane Rosinski)

- “Sedgey” is a male trapped in Orrington and adopted by Center Drive School. “Sedgey” was named after the stream on which it was trapped: the Sedgeunkedunk.

Researchers measuring Sedgey's culmen, or bill length. (Photo by Brittany Marinelli)

- “Cornelia” is a female trapped at the New Gloucester Fish Hatchery, adopted by the Gray-New Gloucester High School. She had gotten into a fish rearing raceway at the hatchery, making her an easy capture with a long-handled net.

Cornelia perched in a tree nearby right after release. (Photo by Joyce Love)

- “Mellow” is a female trapped at Pine Ponds on Orono Land Trust property and adopted by Old Town High School.

- “Nokomis” is a female trapped in Palmyra and adopted by Nokomis High School.

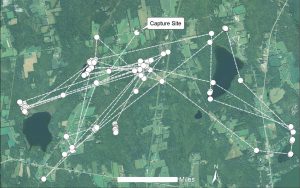

The first four days of movements by Nokomis.

MDIFW hopes to get students from every town in Maine following the five tagged great blue herons online and using the data generated by the solar-powered backpack transmitters in their classrooms. Data can be viewed online via an interactive map, and can be downloaded for use in Google Earth, Microsoft Excel, and ArcGIS. Students involved will not only learn something about great blue herons, but also make the connection that these birds rely on healthy wetlands, both in Maine and beyond. Click here for more information on the Heron Tracking Project, including how to follow the great blue herons once they are tagged and resources for educators interested in using the data in their classrooms.