April 1, 2021 at 12:27 pm

Despite the many challenges that 2020 placed on the world, the Heron Observation Network’s volunteers didn’t skip a beat. Thankfully, outside is the safest place to be during the pandemic, and thus our usual heron colony monitoring efforts carried on in a similar fashion as in past years. For the twelfth year in a row, volunteers trekked to great blue heron colonies in all corners of the state to collect nesting data that is providing a clearer picture of the population’s status. Sixty-eight volunteers and staff monitored 112 great blue heron colonies. They made 200 visits, logged over 320 hours and drove over 4,343 miles.

This is truly a dedicated bunch, because not only did they document 55 active great blue heron colonies with 401 nesting pairs, they also visited sites that turned out to be inactive with no herons to be seen. Both types of data – active and inactive colonies – are equally valuable, though maybe not equally rewarding to document.

volunteer, Barbara Grunden.

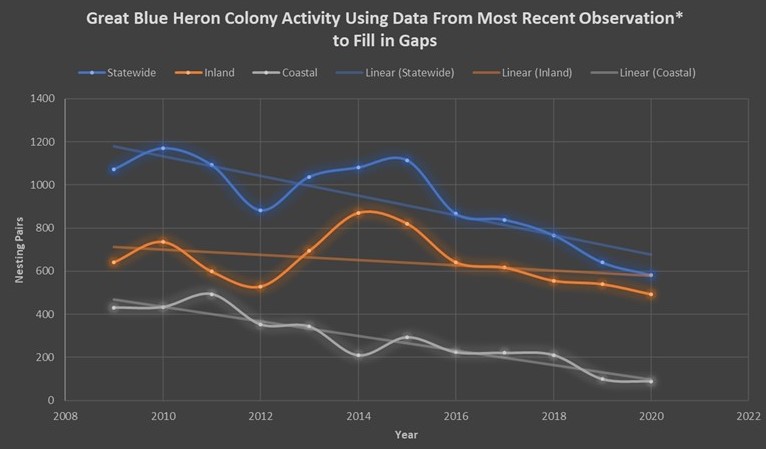

While all the hours and miles and energy that went into monitoring colonies in 2020 ends up as just one more data point on the graph, we are starting to see an overall declining trend in BOTH the inland and coastal colonies. The coastal decline has been occurring for some time, but the big question has been whether the statewide population is in decline and if so, to what degree.

Since 2009, the coastal nesting pairs has declined on average 14.5% each year, with an overall decline of 79.3%. In contrast, the inland nesting pairs has fluctuated since 2009 but declined an average of 1% annually since 2009, with an overall decline of 23%. When looking at the statewide population as a whole, the average annual decline since 2009 is 4.7%, and overall is 45.7%. The number of active colonies across the state has also dropped by 18.4% since 2009. While this statewide decline is due primarily to the losses along the coast, the fact that our inland population has not remained stable or even increased due to a suspected movement of coastal pairs inland, could be alarming.

As I’ve described in the past, the best way to understand whether the changes reflected in our on the ground citizen science monitoring observations is to complete a second population estimate using the dual-frame survey methods as conducted in 2015. The pandemic has caused us to push that survey forward to 2022.

Causes for decline are a big unknown. Predation and disturbance are likely at play. Years ago, our sound recorders pointed to raccoons as the culprits at specific inland colonies. Observations of bald eagles at colonies – both inland and coastal – causing disturbance and going after young and adults, have increased over the years. Colony abandonment has been observed after dewatering of wetlands, and occupation by nesting great horned owls or bald eagles. In our thirteenth year of monitoring, we will continue to document all known or suspected disturbances at colonies, hoping to shed more light on potential limiting factors for nesting great blue herons.

Many thanks to all the Heron Observation Network volunteers, landowners, and IFW staff who have contributed to our monitoring efforts thus far. This would not be possible without their steadfast dedication.