October 21, 2019 at 2:00 pm

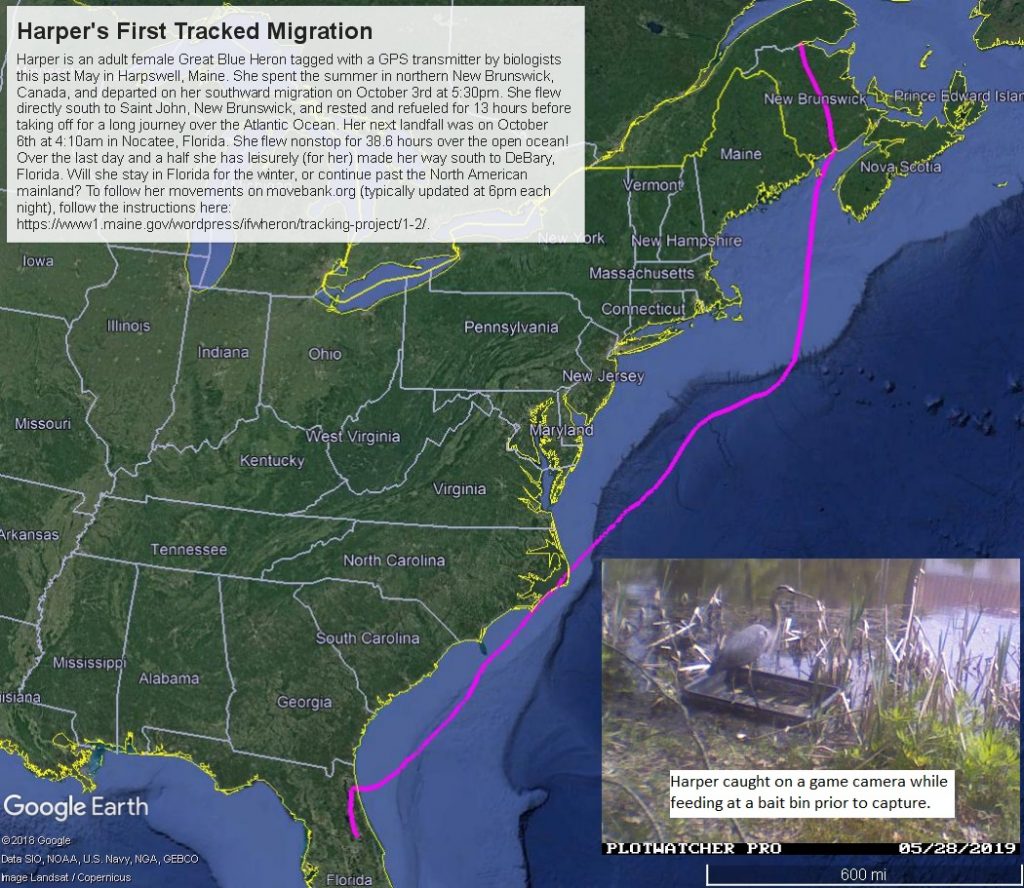

For those who may be late to the party, “Harper” is an adult female great blue heron who was captured and tagged with a GPS transmitter in Harpswell, Maine, by IFW biologists with the help of students from Harpswell Coastal Academy and volunteers with Harpswell Heritage Land Trust. “Harper” received her name from the students and volunteers who spent dozens of hours monitoring game cameras and bait bins, and who woke up at the crack of dawn to help with the capture.

Who knew that the heron we captured that day would do the unexpected, and more than once? She first surprised us by revealing that she was not a Maine breeding heron and instead took off for the northern coast of New Brunswick in June. We had thought that by late May, all herons would be where they intended to spend their summer. Au contraire…her movements in New Brunswick covered four known heron colonies, suggesting she may be prospecting for a place to nest in future years. Another theory is that she is past her prime breeding age and is free to be wherever the fishing is good.

She finally settled on the Quebec side of Chaleur Bay (across from Campbellton, NB), and spent 13 weeks there before it apparently was time to begin her southward migration. On October 3rd she began a deliberate movement south, stopping in a few places in NB, including the coastal town of Saint John. She spent 13 hours there before taking off on a journey across the open ocean that wowed tens of thousands of people.

It is not surprising that a heron who migrates 1,424 miles across open ocean in 38.6 hours would generate some amazement and additional questions – how, why, when, and where it all happened. Here is my best attempt to provide more insight into what we just witnessed and how it fits in with what is known and unknown about great blue herons.

How far, fast, and high did Harper fly?

Total distance= 2,488 miles - Harper’s complete migration path from when she departed Canada on October 3rd at 5:30pm to when she arrived at what appears to be her wintering area in Guajaca Uno, Cuba on October 11th at 4am.

Distance flown nonstop over open ocean = 1,424 miles (2,291 km) – from Saint John, New Brunsick, to Nocatee, Florida, nonstop for 38.6 hours.

Flight speeds during open ocean flight = average was 38 mph (62 kph); max was 67 mph (107 kph).

Altitude during open ocean flight = average was 607 ft (185m), max was 3,103 ft (946m) – these values are actually the height above ellipsoid, which requires a conversion to true height above sea or ground level, and is related to the curvature of the earth at a particular location. We have found these values have some error, so they need to be considered somewhat relative measures.

Typical flight speed for herons (not during migration) = average is 24 mph, but ranges from 9-60 mph, based on flight data of five Maine GPS-tagged herons (Dolinski 2019). Typical altitude (not during migration) = average is 164 ft, but ranges from 3-3,000 ft above ground level, based on flight data of five Maine GPS-tagged herons (Dolinski 2019).

How and why fly fast and high?

Dolinski (2019) also found that herons increased their flight altitudes as they flew at faster speeds, or more likely, flying at greater altitudes facilitated faster flight. Birds generally fly faster at higher altitudes. Higher wind speeds may occur at higher altitudes, so it would be beneficial to fly higher when there’s a need to go faster. Faster flight speed will allow a heron to cover a greater distance in a shorter amount of time, ultimately conserving energy.

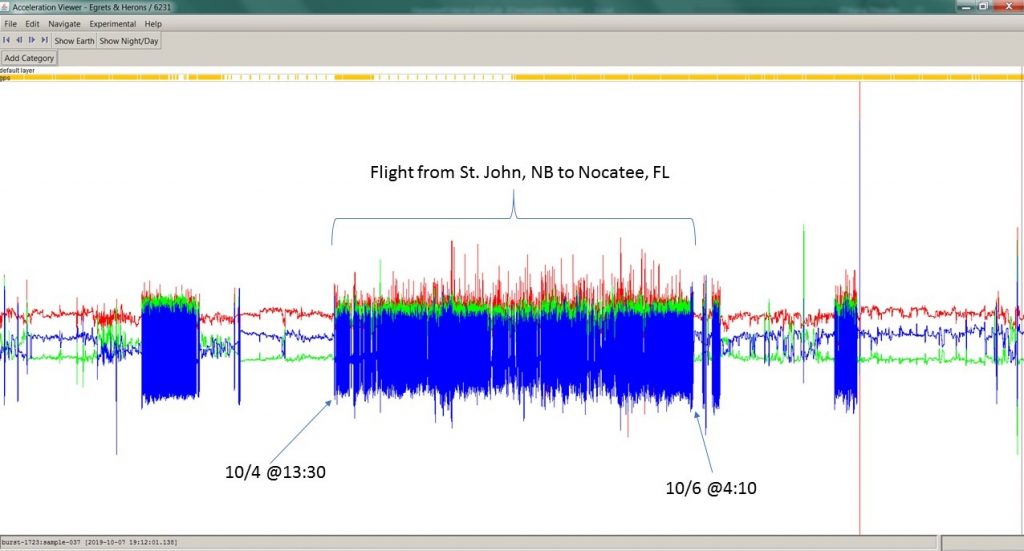

Perhaps Harper hitched a ride on a ship?

While herons and other birds certainly hitch rides on boats, especially when exhausted or trying to escape foul weather or a predator, we know from her transmitter that she was flying that whole way. Her transmitter has an accelerometer which records her activity level, similar to a FitBit. Below is the data from the accelerometer.

Why fly out over the open ocean and not hug the coast and have a chance to rest and feed?

Some of our tagged herons have made their migrations over land for most or part of the way. We don’t know why Harper flew for so long so far from the coast. The night she departed Saint John, New Brunswick, there was a strong north wind that may have partly dictated her direction for at least the beginning of her journey. She did duck in to Florida to refuel and then “island hopped” by stopping in The Bahamas before making it to Cuba.

How often did Harper stop during migration?

Before her marathon open ocean flight, Harper stopped once for 13 hours in Saint John, New Brunswick. Once she arrived in Florida, she stopped five times (Nocatee, St. Johns, Hastings, DeBary, Orlando) in two days, before heading back out over the ocean. She then stopped three times in the Bahamas over the course of 13 hours, then took off for Cuba. She followed the north coast of Cuba, stopping once in Abelardo for 10 hours before arriving at what we believe is her wintering area in Guajaca Uno.

She flew right over the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Why didn’t she stop there to rest and refuel?

It is hard to know exactly why an individual makes certain decisions about where to fly and when and where to stop. The Outer Banks would be a likely place for a great blue heron to stop and forage. Our guess is that she didn’t need to stop or didn’t have a good opportunity to do so. We suspect weather conditions, including wind speed and direction play an important role in these decisions.

Did Harper fly by herself, or as part of a flock?

We don’t know for certain whether she was alone or with others. Many people have observed small groups of herons either flying high or resting together during times consistent with the timing of migration. It is believed that great blue herons migrate in groups of 6-12.

Where is the transmitter located? How would we know if we are seeing Harper or another GPS-tagged heron?

The transmitter is a rectangular box measuring 1" x 2.5" and is on its back. Even if the bird has preened its feathers over it, it may appear as a hump on its back with three short antennas sticking out. All the tagged herons also have a silver leg band. Below are some photos of our tagged birds showing how visible the transmitter is in different situations.

-

Snark preening at his nest. -

Cornelia resting right after her release. -

Snark photographed in Vero Beach, FL. -

Cornelia, just after release before she flew away. The transmitter is most obvious here because she has not yet had the opportunity to preen her feathers around it. Note the silver leg band, too.

Why do some great blue herons migrate long distances but others stay year-round in places like Connecticut, New Jersey, and other states further south?

There must be ice-free foraging areas in order to support a wintering heron. Here in Maine and further north, too much of our wetlands and coastlines freeze over, and there is too much snow cover in the uplands, severely limiting their access to food. In more southern states where it is not as cold, herons will remain throughout the winter. For instance, “Big Blue” is a great blue heron whose last six years of GPS-tag data shows he nests and winters within 13 square miles on Lake Norman in Cornelius, North Carolina.

Where are the great blue herons I am seeing (fill in your location) from and where do they spend the winter?

It is really hard to know without tracking individuals. Herons generally move south for the winter, but they sometimes disperse to the north of their nesting area before heading south. Depending on how far south you are, you may have great blue herons there during the winter, or at least part of it, so some may be yearlong residents.

Where are the other tagged herons, Cornelia and Nokomis?

We have not received data downloads from our other two tagged herons since September, when they were still in Maine. We have seen a pattern of less downloads in the fall prior to migration. In past years, we have had similar situations of no data for weeks and even months. Eventually, once the battery is fully charged and they are within good cell coverage, the birds “pop up” somewhere either along their migration route or in their wintering area. We will update our Facebook page when this occurs.

Why is it that sometimes the data on Movebank are not updated each night (i.e., it shows an old date for the last location)? Does this mean something happened to the heron?

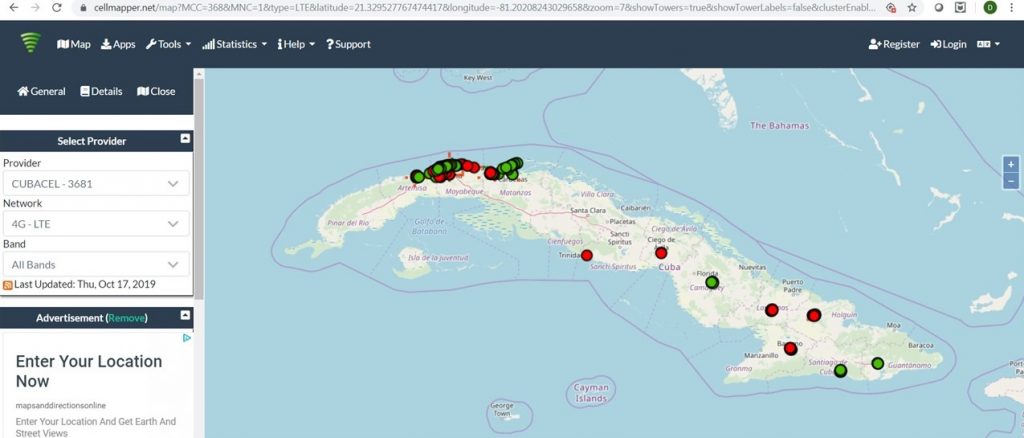

Sometimes, the transmitter is unable to make a connection through the cell network; most often this is when the cell coverage in an area is poor or the transmitter’s battery is low. For Harper, it looks like she is settling in an area of Cuba where there isn't great cell coverage (see the map of cell towers in Cuba below). We have had a few nights where her data didn’t download as scheduled. However, on the next solid connection, we receive a "data dump" of data that her transmitter had been logging continuously.

Do you think your tagging has affected the habits of Harper and the others?

While this is always a concern and something biologists consider heavily, in looking at Harper’s movement patterns, we do not see any evidence that the transmitter has affected her in a negative way. There are always trade-offs to handling and marking wild animals. However, thus far, we have gained an inordinate amount of new information about these birds’ habits that will help us better conserve the habitats they depend on. Furthermore, we have shared the experience and knowledge with numerous students, volunteers, and the general public, greatly expanding the conservation community.

This work is supported by volunteers, the federal Pittman-Robertson program, the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund, and the Maine Birder Band Fund.

Literature Cited

Dolinski, Lauren. 2019. Landscape Factors Affecting Foraging Flight Altitudes of Great Blue Heron in Maine; Relevance to Wind Energy Development. The Honors College, University of Maine, Orono.