May 7, 2018 at 4:17 pm

Snark in Vero Beach, Florida this past January. Photo by Doug Albert.

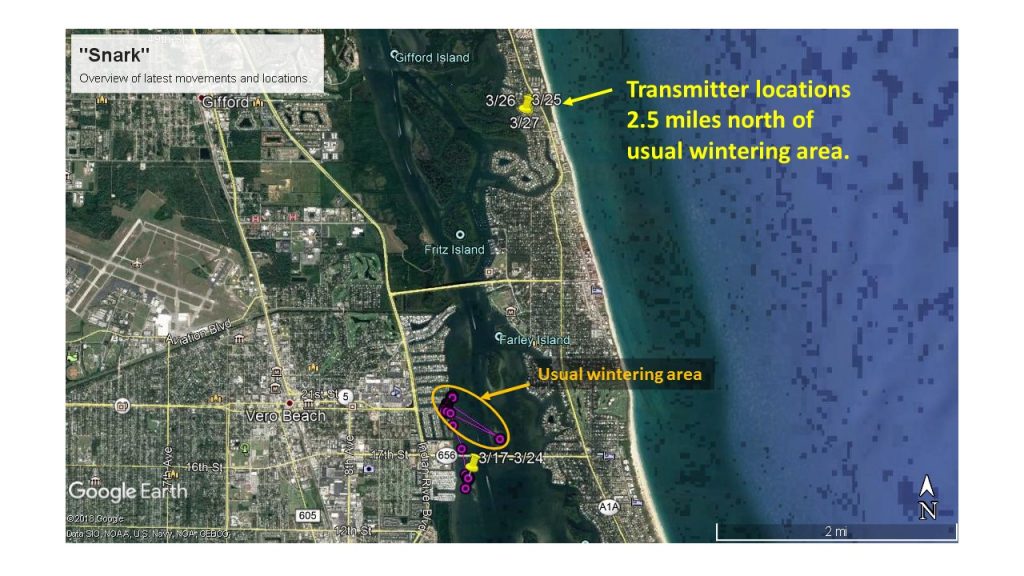

Not all great blue herons migrate, but most of Maine’s breeders choose to spend the winter months in warmer climes at the southern end of the U.S. (Florida) or in another country altogether (Cuba, Bahamas, Haiti). In 2016, we fitted solar-powered GPS transmitters to 5 great blue herons that automatically record GPS locations and transmit data to a website making it extremely convenient for biologists to track the movements of such individuals. However, if something happens to the heron or its transmitter when it is thousands of miles away, the technology is suddenly not very convenient. In mid-March, I was checking movebank.org every evening to see if our tagged herons had begun their northward migration. On March 25th, I noticed Snark, the male tagged in Orrington and named by students at Haworth Academic Center in Bangor, was not in his usual stomping grounds in Vero Beach. Instead he was in the middle of a different neighborhood 2.5 miles to the north. It was possible he had just begun his journey and was in transit, but after a few more nights of no movement, I realized there may be a problem. Map showing Snark’s last movements recorded by his GPS transmitter. His transmitter ended up in a different neighborhood than his usual wintering area, hinting that something may have happened to him.

Map showing Snark’s last movements recorded by his GPS transmitter. His transmitter ended up in a different neighborhood than his usual wintering area, hinting that something may have happened to him.

Snark washed up on an island in the Indian River on March 17th. Photo by John Troutman.

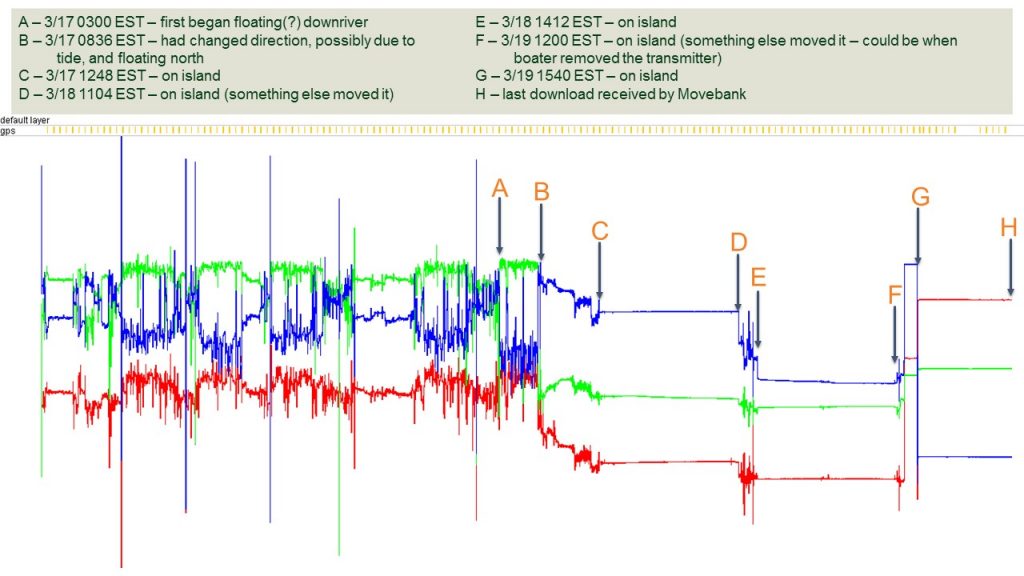

With the help of John Brzorad, of 1000 Herons, we got in touch with Florida’s sister agency to MDIFW, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Biologists Alex Kropp and Anna Deyle came to our aid and visited the neighborhood from which Snark’s transmitter was sending locations. After trying a few houses, Anna knocked on the right door – that of Connie and John Troutman. Mr. Troutman had the transmitter and was glad to hear someone was looking for it! It turns out that Mr. Troutman found Snark washed up on an island while he was out boating in the Indian River. He reported Snark’s USGS bird band and tried contacting U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to see if they knew anything about the transmitter (apparently, the label with our contact info had faded). When Anna showed up asking about it, John was relieved to know it would go back to its rightful owners and be used again for research. After looking more closely at Snark’s movement data, a photograph of Snark when he was first found dead, and the accelerometer data from his transmitter (detailed movement data that show a flatline when an animal is dead), we pieced together the likely cause of Snark’s death: he choked on his midnight snack. At 3 am on March 17th, Snark’s movement pattern changed suddenly. He floated down river for five hours, then floated up river (this area is tidal) for three hours, until washing up onto an island. The photograph of him washed up shows a very bulging neck. We surmised he may have a large fish inside and perhaps died of suffocation. In order to know for sure, we really had to get our hands on his carcass. This is where our Federal sister agency, the USFWS, enters the story.  Map showing a close-up of his last movements. He slowly drifted downriver, then upriver after the tide changed, finally washing up on an island.

Map showing a close-up of his last movements. He slowly drifted downriver, then upriver after the tide changed, finally washing up on an island.

Accelerometer graph showing normal movement patterns prior to A, and more notably, B.

Accelerometer graph showing normal movement patterns prior to A, and more notably, B.

Nineteen days after washing up on shore, Snark’s remains were retrieved by John Troutman and placed on ice for the USFWS to ship back to Maine. We are so very grateful that Mr. Troutman found Snark because not just anyone would be willing to do this! We took a close look at what was left of Snark and alas, found a mass of fish bones in the throat area. We now have a fish skull, several large fish vertebrae, as well as large scales and gill covers, and are working with a PhD student in Florida to identify it to species.

Fish bones and skin found in Snark’s neck area after recovery.

Herons can swallow very large prey. I am often surprised by the size of the fish that are regurgitated into the nest by adults for their young. There are numerous videos on YouTube of a heron swallowing an impressive catch, including this video by HERON volunteer, Richard Spinney. As the viewer, I practically hold my breath until I know for sure it has gone all the way down. After doing a little research, there have been several incidents in which herons have died from eating large prey, but I wonder if this is an important source of mortality for this species? It certainly was significant for Snark.

Snark’s initial capture and release in June 2016. Photo by Alan Maccarone.

Snark was the very first Maine great blue heron captured and tagged with a GPS transmitter. He also is the only one we have successfully recaptured. We have learned a lot from Snark. His wintering habits in a very developed area of Florida contrasted sharply with his elusive behavior here in rural Maine. In just under two years, he traveled over 6,000 miles! We will continue to learn from Snark as we further analyze his movement data, especially compared to the other GPS-tagged herons. We have his transmitter and hope to place it on another great blue heron this spring

Snark at his nest in June 2016. Photo by Jane Rosinski and Gordon Russell.